- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

Ruled Halftone Screens

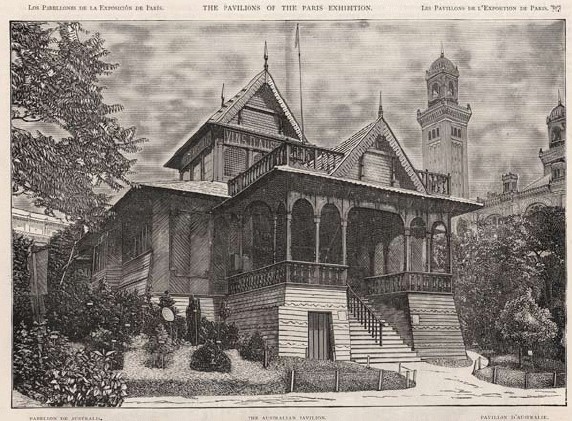

Wood engraving and halftone print. Photographer unknown. The Pavilions of the Paris Exhibition. 1889. 15 x 10" (38.1 x 25.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

This extraordinary sheet comes from a large book celebrating the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1889. The page doesn’t look very impressive until we realize that it shows two photographs, the upper one printed as a wood engraving, the lower as a primitive mechanical halftone. Here we find the old and the new locked up together in a letterpress form. Metal type even shows up on the same sheet—so we have letters made in a lead alloy, hand-generated marks in boxwood, and a chemically etched copper plate tacked onto a wooden support, all working together to generate our sheet. This picture indisputably comes from a photograph, simply because it shows no evidence of the hand. In each case the photographer has stood somewhat to the side of the building, to show its shape, and in both cases he used a fairly wide-angle lens.

Wood engraving and halftone print. Photographer unknown. The Pavilions of the Paris Exhibition. 1889. 15 x 10" (38.1 x 25.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

No doubt this was an old rapid rectilinear lens, a symmetrical design that could be stopped way down to produce excellent wide-angle pictures many years before the invention of the more refined anastigmat lens, in 1898. To top it all off, the pictures, made in Paris, use the standard European format of eighteen by twenty-four centimeters. This was the whole-plate size on that side of the Atlantic in the late nineteenth century, and one of the American tragedies is that we adopted the somewhat turgid eight-by-ten-inch shape instead of this elegant form. The size of the pictures has been slightly changed in the reproductions; the proportions alter a bit throughout the book according to the designer’s layout of each page. The halftone print is nowhere near as good as the wood engraving above it. When I say “good” I simply mean that the new method doesn’t have the clarity and tonal range of the old.

There is a person on the porch—maybe such distractions were eliminated from the wood engraving—and the background, if muddled, is much more realistic. We could also ask whether the building in the wood engraving had been completed when the book went to press—perhaps it was unfinished, and the photograph provided most of the information needed for the reproduction but the reality wasn’t there for the rest. Whatever the case, mechanical reproduction, freed from the judgments of an engraver, contributed to the falsehood that photographs portray some sort of truth about the world from which they derive.