- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

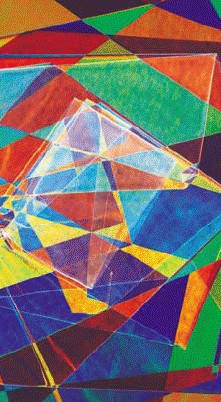

Offset as an art medium

Photo offset lithography. Joan Lyons. Untitled, from the portfolio Presences. 1980. 22 1/4 x 16 1/2" (56.5 x 41.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Joan Lyons. Lyons is one of relatively few artists who have championed photo offset as a creative medium. This multipass print was derived from a twenty-by-twenty-four-inch Polaroid.

Not too many artists use photo offset lithography as their primary medium. I am one, having done my best work in ink on a single-color offset press (long since junked). Joan Lyons, who made the picture on the left, is another. Syl Labrot—now dead—did remarkable color work in offset, and Lyons, Labrot, Scott Hyde, and Carl Sesto pretty much make up the group I know about. I am sure there are others out there but probably not too many. This is not surprising, because production offset presses are large, expensive, dirty, and dangerous. They had one at Yale in the ’70s, in the graduate design department, but it nearly scalped a student once and they had to get rid of it. One has to be extremely careful around sticky ink moving on rotary cylinders at high speed. As if this wasn’t bad enough, the artist using this medium also needs to have a copy camera, vacuum frame, arc lamp, and tons of other bits and pieces to have a functioning offset shop.

Photo offset lithography. Scott Hyde. Folded cellophane – Polarized x 3. 1966. 8 1/2 x 4 3/4" (21.6 x 12 cm) © Scott Hyde.

It is unfortunate that the artist using offset is so rare, because it is a great medium. Ink can be piled up in multiple layers, editions in the few hundreds are easy, and if the inks are chosen carefully, work made this way can be extremely permanent. Small art shops exist for intaglio processes, stone lithography, and fancy letterpress, and some even have offset proof presses on hand, but the pure-offset art shop never really happened. It is even less likely today, because the new digital printing technologies lend themselves beautifully to atelier-scale work. A big inkjet printer, high-end Macintosh computer, and flatbed scanner together cost a fraction of the investment needed for a new offset press. A tremendous number of older presses are out there in daily use, but ultimately offset will most likely fade away except for large-edition work, done by web printing, and substantial book projects that can justify the initial investment in preparatory work. Maybe fine little two- or four-color presses will then be available cheap, and perhaps a few enterprising souls will grab them and set up private shops, to make art with this great medium even as the digital revolution takes over.

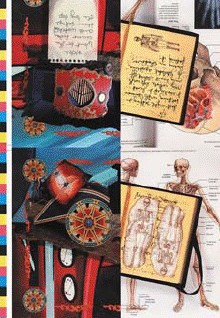

Photo offset press sheet. Carl Sesto. Press sheet. 1994. 15 3/4 x 11 1/4" (40 x 28.6 cm). From Ordinary Events (Boston: SMFA Press, 1994). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Carl Sesto. This uncut press sheet shows four pages of a book printed by the artist himself on a small offset press.

A good friend of mine has a printing company with, hidden away among the behemoths, a beautiful little nineteen-by-twenty-five-inch, five-color Heidelberg press. Every time I visit him I make a point of walking by that press to see if they are still using it. When new it must have cost upwards of $500,000, but once obsolete, it won’t be worth a nickel. The last time I visited the plant I surreptitiously paced off the length of the machine to see just how much room it took. I could just manage to fit it into my basement workroom.