- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

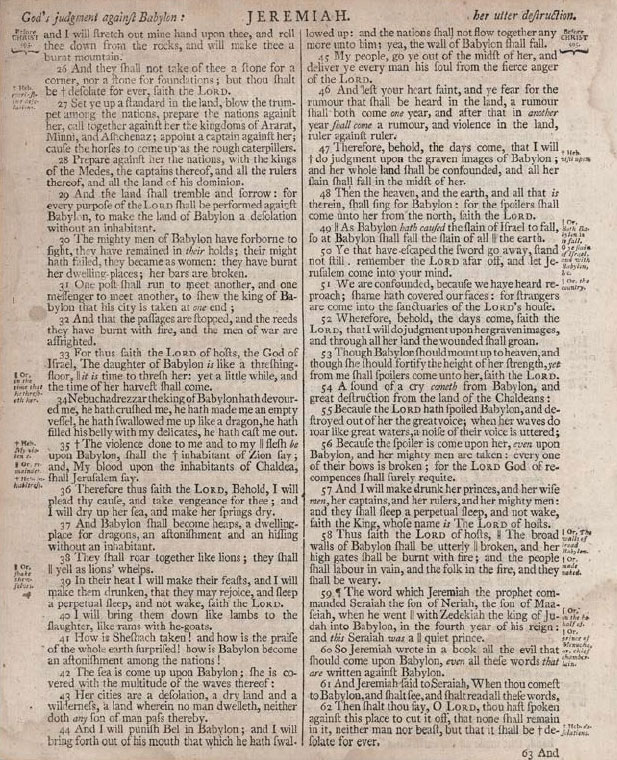

Letterpress

Letterpress from metal type. Mark and Charles Kerr, Edinburgh, printers. Holy Bible, page from Jeremiah 51. 1795. 9 11/16 x 8" (24.6 x 20.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Handwritten manuscripts were costly to make, and could exist only in limited numbers, available to the well-to-do and the powerful. In the mid-fifteenth century, in their efforts to produce less expensive versions of written language, printers began to use metal type, unleashing the great revolution of language-based information available to the masses. Prince and pauper alike got the same information from the printed page, and I have always thought that democracy as we know it would have been impossible without this innovation. The use of metal type spread rapidly, and over the 400 years from 1500 to 1900 the technology of printing words by making them up out of little metal letters in relief remained basically unchanged.

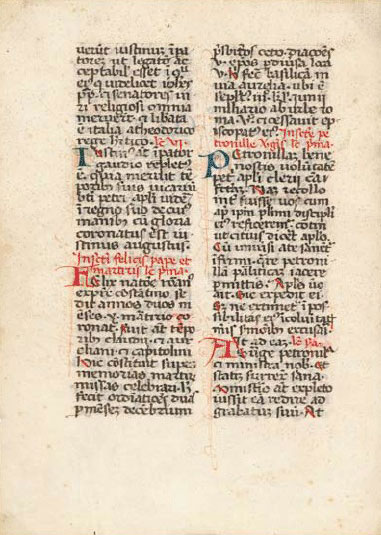

Hand lettering. Artist unknown. Page from a missal. c. 1350. 5 3/4 x 4 1/8" (14.6 x 10.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Technological innovation tends to derive from need, and the development of printing from moveable type was such an innovation that its initial technology did not require much further development for this astonishingly long period.

This small and simple manuscript page dates from the fourteenth century. The letters are run-of-the-mill, written rapidly by a scribe on a sheet of calfskin. This is not part of a large and splendid Bible, worth thousands of dollars; rather it is a remnant of a Catholic missal that I bought in a junk shop for $20 some years ago. Before the invention of lead type such pages existed by the hundreds of thousands. Bound up in books, they were the primary carriers of language in a fixed form, as opposed to the fluid and changeable information buried in the spoken word.

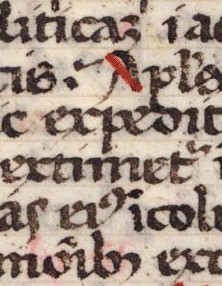

Detail from Hand lettering. Artist unknown. Page from a missal. c. 1350. 5 3/4 x 4 1/8" (14.6 x 10.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. A small manuscript page written in a southern Gothic book hand. Handwritten letters can vary according to their neighbors, and individual letters often run together. This practice gives a strong identity to the words, and reinforces the fact that letters by themselves mean nothing; content only exists when words and sentences are formed.

Detail from Hand lettering. Artist unknown. Page from a missal. c. 1350. 5 3/4 x 4 1/8" (14.6 x 10.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. A small manuscript page written in a southern Gothic book hand. Handwritten letters can vary according to their neighbors, and individual letters often run together. This practice gives a strong identity to the words, and reinforces the fact that letters by themselves mean nothing; content only exists when words and sentences are formed.