- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

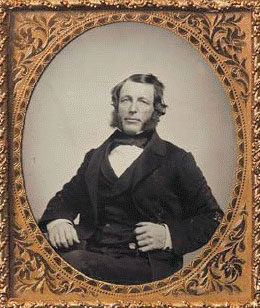

Ambrotypes and tintypes

Ambrotype. Photographer unknown. Portrait of a man. c. 1880. 3 5/16 x 2 3/4" (8.4 x 7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Most photographers who have worked in the darkroom are aware that negatives can sometimes appear as positives. Often we will lift an underexposed negative out of the fixer, disappointed that it is of insufficient density, and find that it suddenly appears as a positive. This occurs when the silver deposit is illuminated by the overhead light but we see it against a dark background, perhaps the old darkroom trays made of black rubber. The silver, which appears light gray, shows as a positive instead of a negative, since it is much lighter than the background against which we see it. This phenomenon was noticed early on, and some wet-plate photographers turned it to use by intentionally underexposing their plates, then coating the back of the glass with black paint. The resulting pictures—unique, direct-positive images— were called ambrotypes. Usually small, they were put in cases and entered the same market as the dying daguerreotype.

Tintype. Photographer unknown. Arthur Cleveland. c. 1895. 4 x 3 1/4" (10.2 x 8.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. Arthur Cleveland grew up and lived most of his life in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. As a middle-aged man his portrait was painted by Andrew Wyeth.

The tintype was a variant of this process, made by applying the wet plate coating not to glass but to a sheet of black-lacquered metal. The tintype survived for years. It was cheap, easy to do in a small size, and because the metal base didn’t absorb water it could be exposed, developed, dried, and then immediately given to a tourist or other traveling customer to carry away. Part of the problem with both the ambrotype and the tintype was that they were unique—each exposure produced just one picture. Like the daguerreotype, every one still around once sat in the camera facing its subject; it is a relic of the origins of photography. Another drawback was that the highlights were always gray—the beautiful white of paper, capable of holding a long range of tones, did not exist for either process.