- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

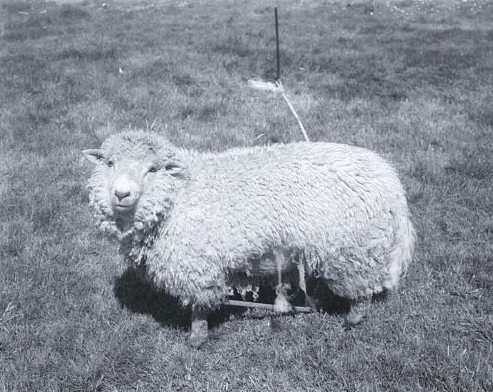

Dye-sublimation printing

Dye sublimation print. Richard Benson. Tethered Sheep. 1995 (Printed 1998). 7 1/2 x 9 1/2" (19 x 24.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Richard Benson. In the dye sublimation process, originally refined for military use, tiny heating elements transfer dyes to a paper support. This particular print was made using a single layer of black dye.

Very early on in the digital upheaval a completely new kind of photographic printer appeared. Called the “dye sublimation” printer, it used tiny heating elements to force a dye onto a receiver sheet. The prints it made were usually eight by ten inches in size, although I remember one model that went up to eleven by seventeen; I don’t know of any that went larger than that. The first one I saw was at a small digital workshop up in Camden, Maine, that was funded by the Eastman Kodak Company. The printer, called a Kodak 7000, was an odd-looking device, plain in design, with a pair of handles on the front. It only took me a minute to realize that it had been designed to slip into a rack, like those that held radio equipment in the ham-radio age. I asked the Kodak technician why the machines were designed that way and he said it was so they could fit into the racks of the B-52 bombers for which they were made. These printers were developed so that instant color prints of targets could be generated right on the plane. Like so much other technology that we love, this one came to us from the military.

Detail of Dye sublimation print. Richard Benson. Tethered Sheep. 1995 (Printed 1998). 7 1/2 x 9 1/2" (19 x 24.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Richard Benson. This twenty-five-times enlargement from the print shows the soft squares of tone generated from the black dye layer in this black and white print. Unlike a hard halftone or stochastic dot, these patches of dye have variable tonality, deriving from the modulated heat used to transfer the dye.

The dye-sub printer uses a long roll of clear acetate holding solid layers of dye in the three subtractive primaries and black. When a print is made, a special sheet of paper is drawn into the printer and held next to one of the dye layers on its acetate support. Together they are wrapped around a drum. A set of heating elements 200 per linear inch is lined up across the drum, to be selectively fired by the digital file holding the picture information for that color. As the paper/ dye combination moves beneath these heaters, the dye is activated and moves over to the paper receiver. Once a single layer of dye has transferred, the paper is aligned with the section of the acetate sheet holding the next color and the heating operation is repeated, again driven by a file for that color. This is done four times; finally the machine ejects a completed color print. After a single print is made, the length of the acetate support holding the used-up areas is rolled up and a fresh section is ready for the next print.

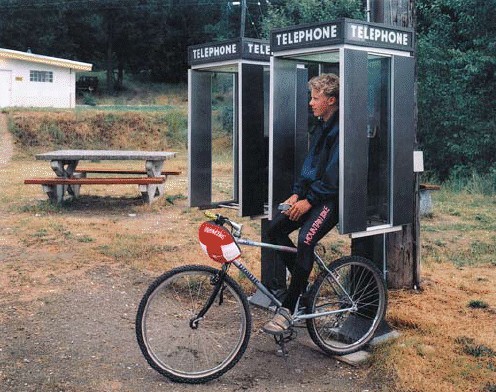

Dye sublimation print. Richard Benson. Boy on Bicycle. 1995 (Printed 1998). 7 1/2 x 9 1/2" (19 x 24.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Richard Benson. This dye sublimation print has four layers of dye: cyan, magenta, yellow, and black. There are about two hundred tonal elements per linear inch, but because each small patch of color has soft edges and incorporates internal variants of tone and color, the print appears to have a far higher resolution.

Dye sublimation prints look very much like traditional chromogenic prints. They have terrific colors, saturated and smooth, and their surface is usually moderately gloss (although matte paper supports are also made). These printers can also make superb black and white prints, using only the black section of the color band. When examined by magnifying glass the dye appears in soft squares, 40,000 to the square inch. Because the values within each square vary in tone and color, they assemble together smoothly to the unaided eye and look like a high-resolution continuous-tone print. The old halftone screen, in sharply defined solid colors, shows up easily at this same resolution, but the dye sub’s soft, particulate structure disappears, just like the stippling in chromolithography.

Detail of Dye sublimation print. Richard Benson. Boy on Bicycle. 1995 (Printed 1998). 7 1/2 x 9 1/2" (19 x 24.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Richard Benson. These patches from the color print are enlarged approximately twenty-five times.