- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

Multipass intaglio

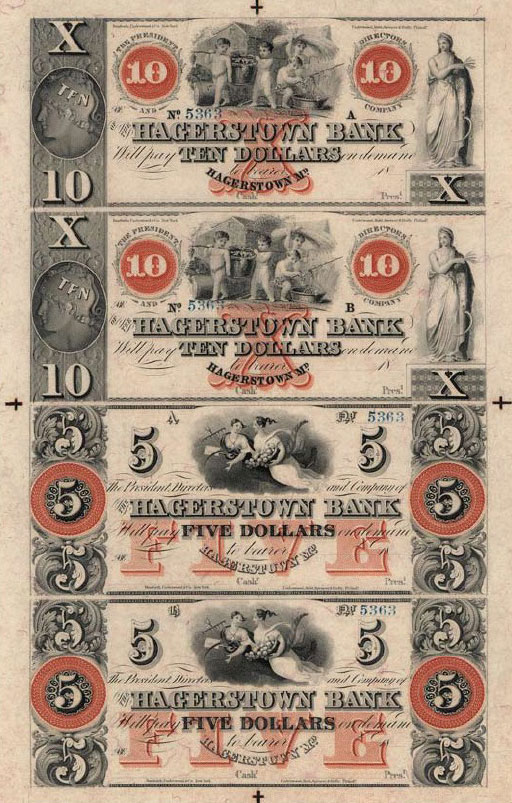

Two-color steel engraving. Danforth, Underwood & Company. Uncut banknote proof sheet. c. 1839. 12 1/4 x 7 3/4" (31.1 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. By the mid-nineteenth century, paper money was often printed in color. This uncut sheet shows registration marks on its border.

Sometimes one comes across a piece of printed paper that is pure pleasure to look at. This sheet of currency, one of the most beautiful things I own, fits nicely into our examination of multiple-impression printing. It is an uncut sheet, intaglio printed, that retains its original borders and registration marks. The bills were probably printed sometime between 1839 and 1842, because the names of two banknote-engraving companies appear on each bill, and we have records that one of the companies was created in 1839 and that they combined into a single organization, with a different name, in 1842. In the early years of the nineteenth century banks issued a huge variety of currencies, which were printed by many engravers. In 1863 the U.S. government put a stop to this and became the country’s sole issuer of paper money.

Detail of Two-color steel engraving. Danforth, Underwood & Company. Uncut banknote proof sheet. c. 1839. 12 1/4 x 7 3/4" (31.1 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. Mechanical methods capable of decorative details such as these had appeared by the mid-nineteenth century. The filigreed orange circle around the fives was engraved or etched by a pantograph working from a larger image.

At about the same time, virtually all the small printers of currency merged to become the American Bank Note Company, which remained active until electronic banking reduced the need for paper bills in the late 1990s. Unlike the older etchings and engravings, this sheet was not printed by hand: although intaglio printing remains a hand process for “art” prints even today, mechanical methods emerged early on to meet the need for huge editions of currency, postage stamps, and fancy certificates. The paper is very thin, about .002 inches thick (.05 mm), and the quality of the registration speaks of a sheet printed dry, instead of dampened, as hand printing required. The two colors on this sheet—black as the key impression, orange as the second—were both printed from steel plates that had been etched and then engraved.

The four register marks—the crosses in the margins—demonstrate the oldest method of aligning multiple impressions. On modern presses, in almost all of the processes, the impression is light and the paper undergoes little distortion. Before the invention of rotogravure in the late nineteenth century, though, intaglio always distorted the sheet severely, and a second impression could never be aligned exactly with the first. The compromise solution to this problem was to use four register marks on the borders, arranged like those on the sheet of currency shown, which could be aligned as well as possible. This gave the center of the sheet the best “fit”; registration errors increased toward the edges. In the early years of the United States, currency was printed by plain old letterpress, but it always had a shaky reputation and coin was regarded as the genuine specie. It is no wonder that intaglio printing became the standard for money because its rich appearance gives some sense of solidity to the bills. Today there are hordes of currency collectors and I have always thought part of the attraction they feel toward old money is based on its visual beauty.