- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

Weaving

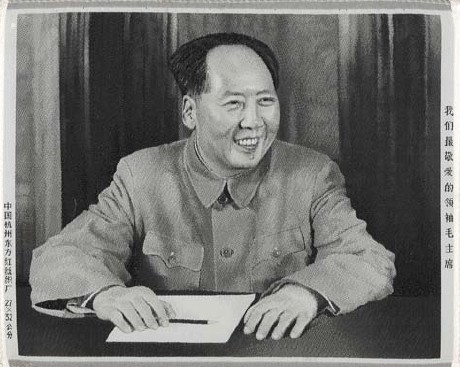

Weaving. Photographer unknown. Chairman Mao. c. 1950. 11 1/4 x 14 1/8" (28.5 x 35.8 cm). Printed by Silk Line. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. Binary information was probably first used in mechanized textile looms, as early as the eighteenth century. This contemporary example achieves about thirty-two levels of tone using only black and white threads (not counting the transparent threads in the weft). The process simultaneously produces positive and negative images on opposite sides of the fabric.

This piece of cloth,which can be viewed from both front and back, is a picture of Chairman Mao. Probably woven in the 1980s, it is nevertheless full of lessons about the history and technique of printing and photography. First of all, it is a piece of weaving that holds a representational picture.

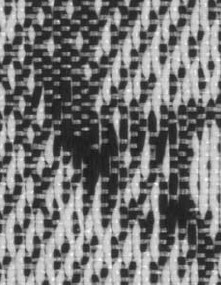

Detail of Weaving. Photographer unknown. Chairman Mao. c. 1950. 11 1/4 x 14 1/8" (28.5 x 35.8 cm). Printed by Silk Line. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Pictures of all kinds—representational, decorative, symbolic—have long appeared in weaving, but this one was made with a Jacquard-type loom, a loom driven by punch cards that translated the tones of the image into patterns of stitches displaying values from dark to light. Invented at the start of the nineteenth century, these looms are the first known practical instance of binary numerical data being applied to a visual end. The one that wove this was already obsolete when it did its weaving. Chairman Mao might be made of threads woven into cloth, but he unquestionably started out as a photograph. This is the second lesson from this weaving. We should understand that the description of the world made by lens and camera is radically unlike that of traditional artists.

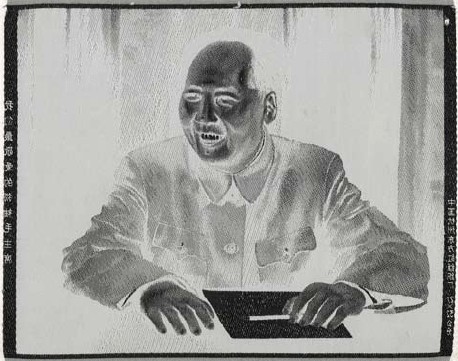

Weaving. Photographer unknown. Back of Chairman Mao. c. 1950. 11 1/4 x 14 1/8" (28.5 x 35.8 cm). Printed by Silk Line, c. 1980. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

When a portrait painter made a picture of a famous figure, the form and content of the picture inevitably revealed what was thought about the subject—what the artist, the sitter, or both wished to have projected to the viewing audience. Photography, on the other hand, makes its pictures out of reality, and brings to the viewer objects and structures whose description is far from the traditional ideals. Mao’s pudgy hands, the tabletop on which they rest, and the inactive pencil were the photographer’s props, but their appearance comes from the world itself, without the embellishments of traditional art. We must not confuse a photograph with the world from which it is made, but there is little question that photography’s connection to that world gives it a radically new visual character when compared to the old handmade pictures.

Detail of Weaving. Photographer unknown. Back of Chairman Mao. c. 1950. 11 1/4 x 14 1/8" (28.5 x 35.8 cm). Printed by Silk Line. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The third lesson comes from the back of the cloth. The weaving was done with two sets of threads in the weft: one black, the other white. Tones were made by grouping stitches in a grid and controlling the amount of white and black shown in any given grid area. The interesting thing is that as white threads were shown on the front, the black threads had to move to the back, and vice versa. So the positive image on the front generated a negative one on the back. This is a beautiful way to see the relationship between positive and negative: if you have an even tonal field and remove a positive picture from it, a reversed negative image remains. Almost all color photography would end up using this principle to generate positive images in one step.