- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

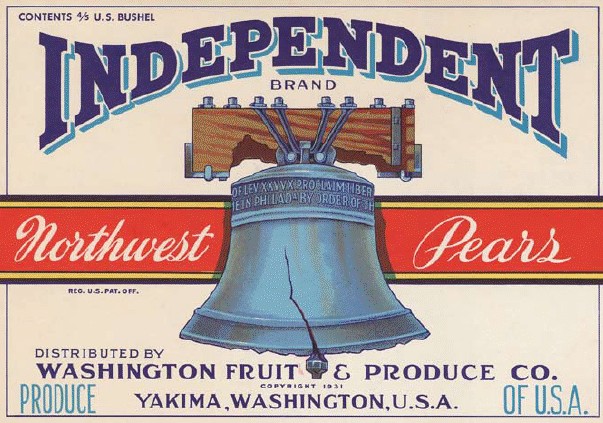

The nature of offset printing

Photo offset lithography. Artist unknown. Label for fruit box, Independent Brand Northwest Pears. c. 1950. 6 15/16 x 9 13/16" (17.7 x 25 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson ©Washington Fruit and Produce. “Photo offset” lithography first came into widespread use shortly after World War II as a means of printing colorful labels for fruit and vegetable boxes. They could be produced very inexpensively in short runs, without the need for the costly copper or zinc plates that would have been required for letterpress printing.

Relief printing (as halftone-based letterpress), gravure, and collotype gave the printing trades three terrific systems for reproducing photographs. These processes had their heydays from about 1880 until 1960—fully eighty years—and they were directly responsible for photography’s move out of the darkroom, with its chemical print, and into its modern role as the great visual data-transport system of today. Through the early years of the twentieth century, another process slowly took form that would prove to be the giant of all picture-printing processes. This was photo offset lithography, which, in its final form, brought together lithographic chemistry, lightweight and inexpensive printing plates, and simple, completely photographic data input to the printing press. I will try to be restrained in describing offset (as we casually called it), but it is both my trade and my chief love of all the ink-printing methods, so even while being cautious I will probably say too much about it.

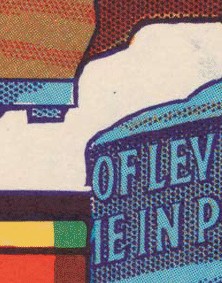

Detail of Photo offset lithography. Artist unknown. Label for fruit box, Independent Brand Northwest Pears. c. 1950. 6 15/16 x 9 13/16" (17.7 x 25 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson ©Washington Fruit and Produce. The fruit label was drawn by hand, then printed with solid colors and coarse halftone screens. The printer used rough approximations of the subtractive primaries, but there are two blues instead of the usual cyan; one blue has a lot of red in it and the other, lighter one is quite green. Many package labels carried specialized colors, which almost always struck the eye with an intensity that halftone-generated mixes of the primaries could not. This technique, called “spot color,” is used to this day in fancy color printing.

More pictures have been printed in offset than by all other methods combined, so a careful examination isn’t such a bad idea. Today we are also witnessing the peak of the process’s development; it is fully integrated with the computer, and through the next years, as digital printing takes on smaller jobs, the offset behemoth will most likely live on, producing superb printed editions of books, catalogs, and magazines. I think it will be around for quite a while yet. The process had its origins in chromolithography.

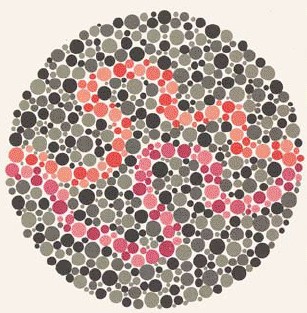

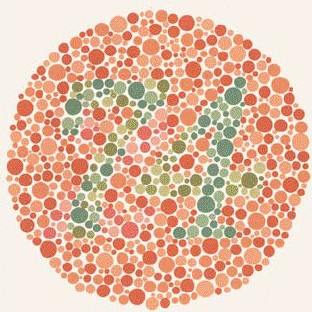

Photo offset lithography. Shinobu Ishihara. Plate from Ishihara’s Tests for Colour-Blindness (Tokyo: Isshinkai, 1966). 1966. Printed by Isshinkai. 3 7/8 x 3 7/8" (9.9 x 9.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © 1959 Kanehara Shuppan Co., Ltd. Tokyo. Developed in the 1930s by Dr. Ishihara in Japan, these beautiful arrays of colored dots, printed by offset, could accurately hold the subtle colors needed to determine slight individual differences in color vision.

Lithography, printing right off the stone surface, could lay down a beautiful solid layer of ink. As soon as light-sensitive metal plates replaced the stones, the halftone, fully refined in letterpress printing, could move into lithography—the old, laborious translation of pictures by hand could be mechanized through the halftone screen. The metal plate and the halftone were vital to the rise of offset, but the central innovation, the one that made it king, was the introduction of the offset blanket. Printers had long known that when a fully inked roller was used to transfer ink to a printing plate, the roller, after the transfer, retained a negative image of the plate, since the ink in the image areas had been removed from it. This observation made clear that a rubber roller could hold an ink image.

Photo offset lithography. Shinobu Ishihara. Plate from Ishihara’s Tests for Colour-Blindness (Tokyo: Isshinkai, 1966). 1966. Printed by Isshinkai. 3 7/8 x 3 7/8" (9.9 x 9.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © 1959 Kanehara Shuppan Co., Ltd. Tokyo

If a clean roller was passed over an inked litho stone, then rolled again onto a sheet of paper, a positive image could be picked up and transferred to the paper. This practice of transferring, or “offsetting,” an image became the core of photo offset lithography: a metal plate was inked, it printed onto a rubber blanket, and that blanket then transferred the image to the paper. The ramifications of this practice were revolutionary.