- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

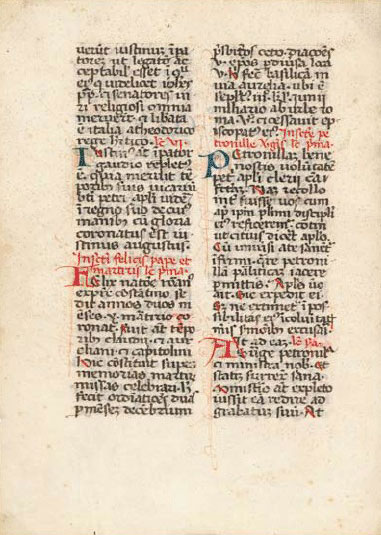

A hand-lettered manuscript page

Hand lettering. Artist unknown. Page from a missal. c. 1350. 5 3/4 x 4 1/8" (14.6 x 10.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. A small manuscript page written in a southern Gothic book hand.

This small and simple manuscript page dates from the fourteenth century. The letters are run-of-the-mill, written rapidly by a scribe on a sheet of calfskin. This is not part of a large and splendid Bible, worth thousands of dollars; rather it is a remnant of a Catholic missal that I bought in a junk shop for $20 some years ago. Before the invention of lead type such pages existed by the hundreds of thousands. Bound up in books, they were the primary carriers of language in a fixed form, as opposed to the fluid and changeable information buried in the spoken word. Centuries before this page was written, human culture had learned the remarkable lesson that language could be laid out, in all its tremendous variety, through the use of a limited set of letters and words.

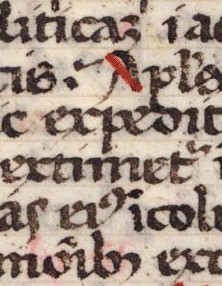

Detail from Hand lettering. Artist unknown. Page from a missal. c. 1350. 5 3/4 x 4 1/8" (14.6 x 10.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. A small manuscript page written in a southern Gothic book hand. Handwritten letters can vary according to their neighbors, and individual letters often run together. This practice gives a strong identity to the words, and reinforces the fact that letters by themselves mean nothing; content only exists when words and sentences are formed.

This is simply astonishing. Not only could the mind direct alterations of the physical world, the building of cities and the plowing of fields, but its workings could also be codified by such a simple set of tools as the letters of the alphabet and their astonishingly versatile arrangement into words and sentences. Once these words were written down they acquired the extraordinary ability to outlast their makers: this page, like our little Dürer woodcut, has managed to last dozens of times longer than the life of the person who made it, even outliving anyone who might have used it for its original purpose.

This persistence has shown that accumulated knowledge, set down in ink on paper, has the ability to last through generations. In the animal kingdom some artifacts do last—pathways and burrows can be used over decades—but by and large the knowledge each individual accumulates through experience dies once the biological shell fails. The written word gave humanity a tool far beyond that of any other animal; it is the perfect Darwinian step to ensure the survival and dominance of the species.