- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

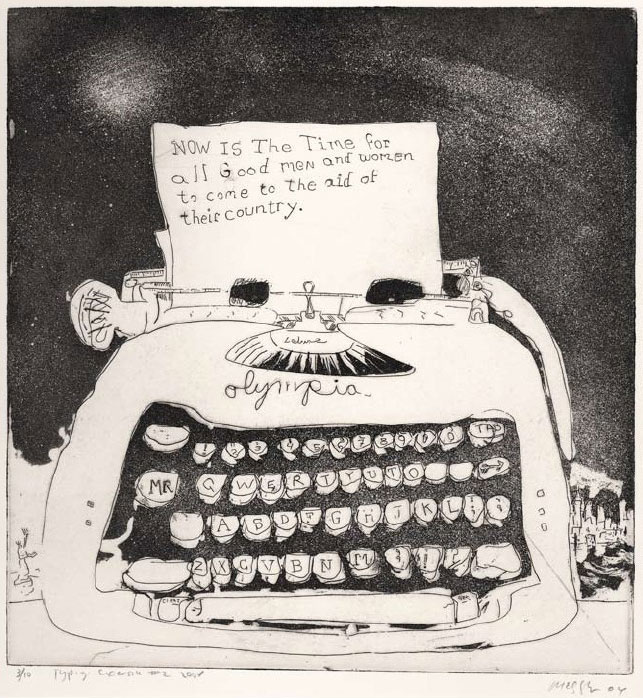

Modern Etching

Etching with aquatint. Sam Messer. Typing Exercise #2. 2004. 11 x 10 1/8" (27.9 x 25.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Sam Messer. Many modern print editions are produced for artists by professional technicians in commercial studios, but this etching with aquatint was made entirely by the artist himself.

This is an etching made by my friend Sam Messer, who teaches at the Yale University School of Art. The print uses linear etching, drawn in the resist with a needle and then chemically etched, but also has large areas of aquatint, creating the darkness in the background and between the typewriter keys. Sam teaches painting and printmaking and after hours goes into the printshop at the School, where students are doing projects, and works alongside them making pictures for himself. Art education is a tough thing to do well and many of us in that trade think this is the best (and perhaps only) really good way to teach: to make your own art along with the students.

So the students come to understand the process as a whole, and can see the complex physical and intellectual activity needed in such work. I don’t raise this subject here to praise Sam, but instead to point out that there are two very different ways in which artists practice printmaking today. The old technologies have survived in schools and privately run workshops, but their technical demands are so intimidating (and dirty) that many artists have chosen to leave that side of the activity to hired professionals. The artist goes to the shop, draws on the plate or stone, and then watches while the skilled technician does the chemical and physical work of producing the print. By engaging in printmaking this way the work can have a physical perfection and slickness not available to most artists who might do the work themselves. But working this way also tends—I believe—to sterilize the work, eliminating all those delights that occur when the holder of the artistic vision skates close to the edge of physical disaster while driving a recalcitrant medium in unexpected directions. Artistic printmaking is a big business; successful artists working with professional ateliers can generate large incomes for themselves and their marketers. The work will be technically perfect—appropriate for a grand living room wall—and will spread the artist’s work far and wide, making multiple copies available at a modest cost compared to that of an original painting. Whatever we think of this practice, it is one of the primary engines that preserves the old technologies long after they have outlived their original uses. Even so, those atelier-produced prints are the antithesis of ones derived entirely from the hand of the artist himself.