- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

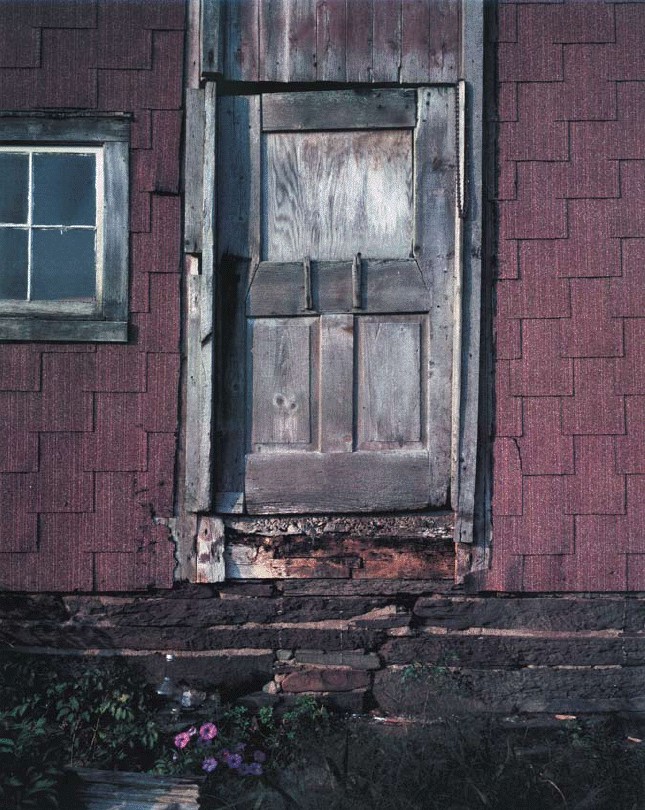

Early inkjet prints

Hewlett-Packard plotter print. Richard Benson. New York State Barn. 1993. 19 3/8 x 15 1/2" (49.2 x 39.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. © Richard Benson.

Even prior to the Iris printer, crude inkjet printers were used to produce architectural drawings. Called “plotters,” these devices used black ink and could turn a computer file into a large drawing to be used in construction projects. The old method of making working copies of drawings was to use a chemical process, such as blueprinting, to reproduce a handmade drawing. The plotter produced a paper version of a drawing that had been made with a computer illustration program, opening the door for the large staffs of draftsmen in architectural firms to become smaller groups of computer operators.

Detail of Hewlett-Packard plotter print. Richard Benson. New York State Barn. 1993. © Richard Benson. The early plotters adapted to photographic use had a relatively coarse dot pattern; this detail is enlarged eight times from the print.

The plotter soon had colored inks, to allow the emulation of drawings with color. (We must always remember the power of color to sell things, whether in a meeting called to sell a wealthy client on an architectural design or on Wal-Mart packaging.) It wasn’t long before these machines were used to make prints of photographs, and by the early 1990s a few manufacturers were producing them as wide-format color photographic printers. This particular print is one I made around that time, by scanning an eight-by-ten-inch Ektachrome transparency with an early drum scanner (to make a thirty-megabyte file, which at the time I thought was immense). The print has pretty good color, only a few streaks, and quite a heavy rendition of the shadow areas. The paper I used was designed to dry the ink rapidly and looks like a sheet of plastic.

The early inkjet printers differed from the Iris printer in that the printing head moved rapidly back and forth across the sheet of paper and after each “pass” the paper advanced a tiny bit so another line of dots could be laid down. The rapidly rotating drum of the Iris, holding a large piece of paper, was eliminated. Since there was no reason to imitate the old halftone, the printers used stochastic screening, and they underwent steady refinement, with new models coming out every year or so. Before long the inkjet printer shook off its architectural roots and became a superb color printing device, laying dots down at a resolution far higher than could be seen by the naked eye. Some of these machines were large, able to print pictures forty-four inches wide by any length, but a whole new type was developed that printed on letter-size or slightly bigger paper. These little machines—desktop printers to accompany the desktop computer—were cheap to buy but expensive to use, because their economic basis was the sale of ink. A printer for letters and family photographs might cost less than $100, but within a very short time the buyer would have spent more than that on ink if a lot of picture printing was done. The machines came with a set of ink cartridges, so the owner became hooked on the new prints well before having to face the $20 cost for each replacement.