- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

Etching and Engraving

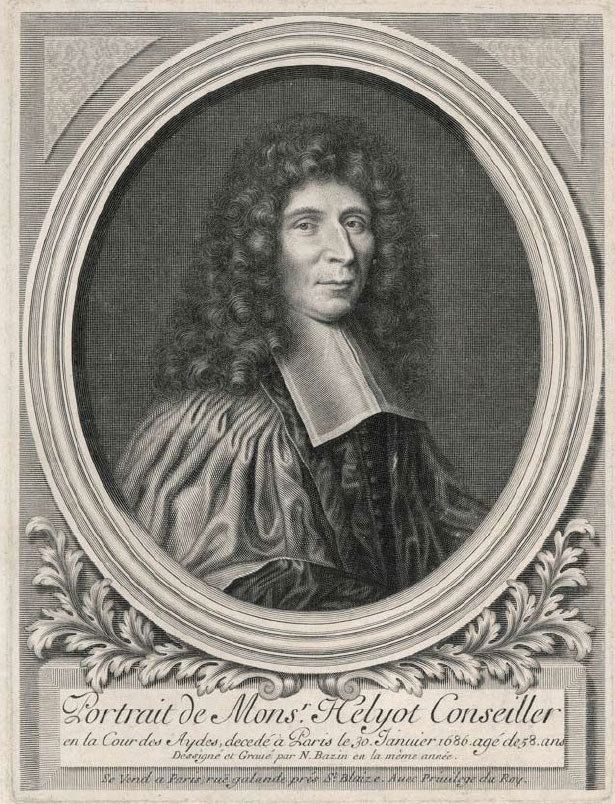

Copper engraving. Nicolas Bazin. Portrait de Monsieur Helyot Conseiller. 1686. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4" (26 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

All copper intaglio printing plates had a smooth polished surface into which the engraved or etched lines were incised. The printer would cover the plate completely with a fairly stiff ink, consisting of pigment in oil, and then wipe off the excess ink using a series of heavily starched cloths scrunched into balls. The wiping gradually removed ink from the plate surface, but the ink in the engraved grooves or lines would remain. After wiping with progressively cleaner cloths, the printer would give the plate a final wiping with the palm of his hand, often after lightly dusting the skin with chalk, to remove every trace of ink from the plate surface. Finally the plate was placed face up on the flat bed of a press that had two rigid rollers between which the bed could move.

Detail of Copper engraving. Nicolas Bazin. Portrait de Monsieur Helyot Conseiller. 1686. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4" (26 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The short strokes begin thin and then broaden as the burin enters the copper. In areas where they portray the desired tone inadequately, the engraver has added small marks between them.

A sheet of damp rag-based paper was set on top of the inked plate; two or more layers of thick felt went on top of that; and the bed was passed between the rollers. The press—properly called a mangle—could exert tremendous pressure on the sandwich of plate, paper, and felt. The pressure was so high that the edges of the plate had to have smooth bevels, to avoid cutting the paper and felts. Once through the press, the paper could be pulled off the plate, and the ink held in the grooves would have been transferred to it. If the relationship between ink, paper, and pressure had been right, the printed lines would have a physical height that no other printing process could produce. No mark in printing can compare with a fine intaglio line.