- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

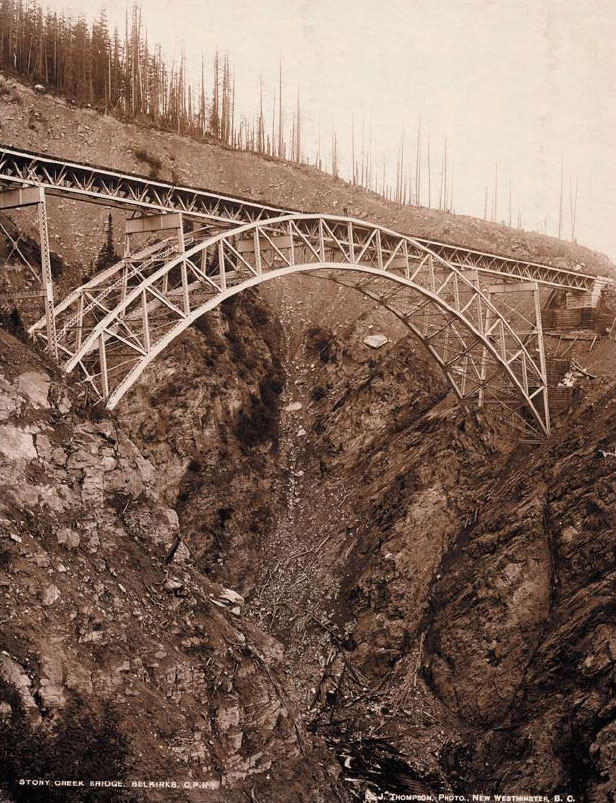

Gelatin-based printing-out paper

Gelatin-based printing-out paper. J. Thompson. Stoney Creek Bridge, Selkirks, C.P.R. c. 1893. 9 1/8 x 7 7/16" (23.2 x 18.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Albumen, the giant of all the nineteenth-century photographic printing mediums, was doomed by the spread of the dry plate, but it underwent a few changes on its way out. Gelatin printing-out paper (POP) was the most widespread of these. Gelatin is a tremendously versatile material, and it was mass produced. (It was a byproduct of animal husbandry—sending the old horse to the glue factory meant it was to become a source not just of glue but of gelatin and animal feed.) Once purified, this organic polymer behaved predictably and lent itself to manufacturing processes with a dependability and ease that albumen did not. A gelatin POP differed from an albumen sheet only in the substitution of gelatin for egg white as the binder that held the silver salts.

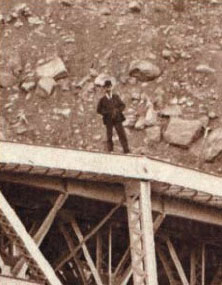

Detail of Gelatin-based printing-out paper. J. Thompson. Stoney Creek Bridge, Selkirks, C.P.R. c. 1893. 9 1/8 x 7 7/16" (23.2 x 18.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. An eight-times enlargement from the original print.

This new paper was still exposed to the sun, it printed out with no developing necessary, and it was gold toned for permanence before fixing. The surface of these new prints, though, was hard and glossy. Albumen’s beautiful, articulated, semigloss surface gave way to the high shine that later modern papers would also have, since they too would be factory coated with gelatin emulsions. While albumen paper had completely disappeared by the 1920s, gelatin printing-out paper continued to be made throughout the twentieth century. Because it produced a superb image that needed no developing, portrait photographers could easily make prints on this paper as proofs for their customers. Being neither gold toned nor fixed, the pictures would gradually darken as they were viewed, so the client would have to come back to the photographer to buy a permanent, final print.