- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

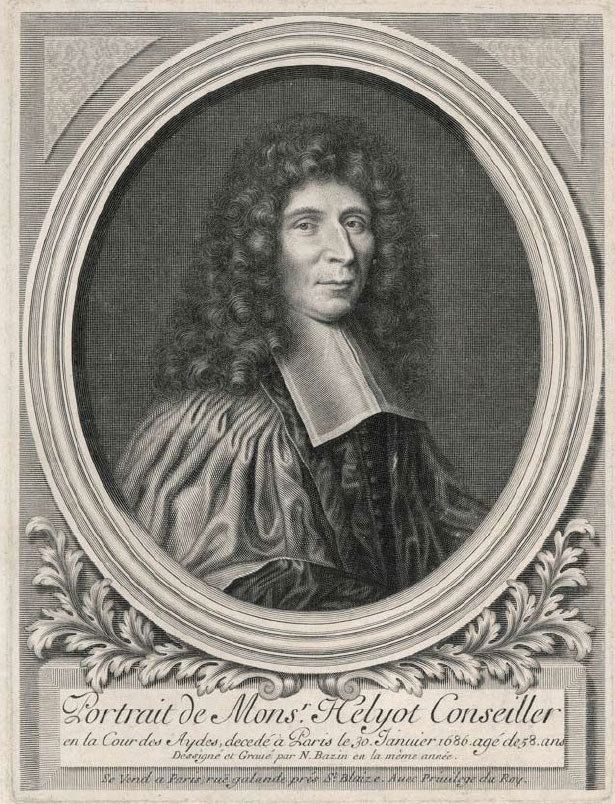

Copper engraving

Copper engraving. Nicolas Bazin. Portrait de Monsieur Helyot Conseiller. 1686. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4" (26 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

With this rather stiff picture of Monsieur Helyot we enter a completely different world from that of wood-based relief prints. The print is a copper engraving that has been printed by the intaglio process. “Intaglio” comes from the Italian “intagliere,” to “cut in” or carve, and describes the class of printing that uses grooves in metal to hold the printing ink. Relief printing, such as the woodcut and the wood engraving, is done by applying ink to the high parts of a printing matrix; intaglio uses the low parts instead. Using a burin, the engraver cuts lines into a polished plate. These lines hold the ink, which the pressure of the printing press transfers to the paper. Engravings were a hugely important pictorial system for centuries, starting to be common in the 1500s and dominating fancy printing until the industrial revolution. Most intaglio printing of this period was done with copper plates.

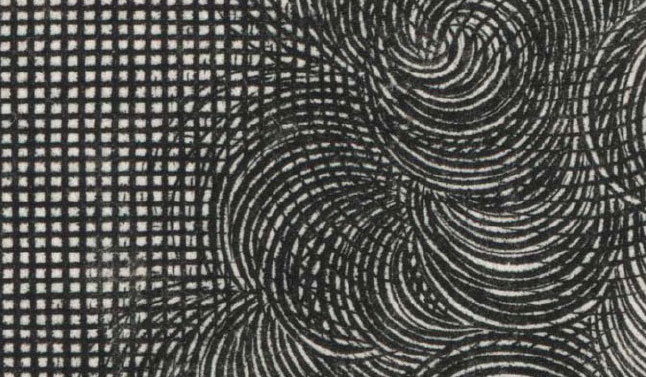

Detail of Copper engraving. Nicolas Bazin. Portrait de Monsieur Helyot Conseiller. 1686. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4" (26 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The curls of Monsieur Helyot’s wig were made by rotating the plate. The square-mesh background was engraved using some sort of straightedge as a guide for the burin.

Copper is a tough material to cut with the burin—it is stringy and resists the tool—but when properly handled it can produce precise and delicate plates that last for many impressions. The burin is a small, lightweight thing, and pushing it in a controlled way across the copper surface is very hard. Much engraving was done instead by holding the tool tightly and moving the plate against it; that way the engraver was using both hands together to guide the line. One easy way of doing this was to rest the plate on a leather pad and rotate it. As a result, many old engravings include a lot of smoothly curved lines, making them the perfect medium for describing the fashionable wigs that swell people wore at one time. We see a perfect example of this in Monsieur Helyot’s absurd hair.

In the hands of a master, copper engraving could make great pictures, but many are awkward. They were often used to make reproductions of paintings, and in the example here, the lettering and the geometric and floral borders are fine, but the articulated cloth shows signs of a struggle on the engraver’s part; the difficulties of cutting the plate have overcome the descriptive requirements of the picture. The face, on the other hand, is beautifully done. Many of the engravings that have survived in museum and private collections are terrific but a vast number are simply terrible, because of the difficulties of engraving the copper.