- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

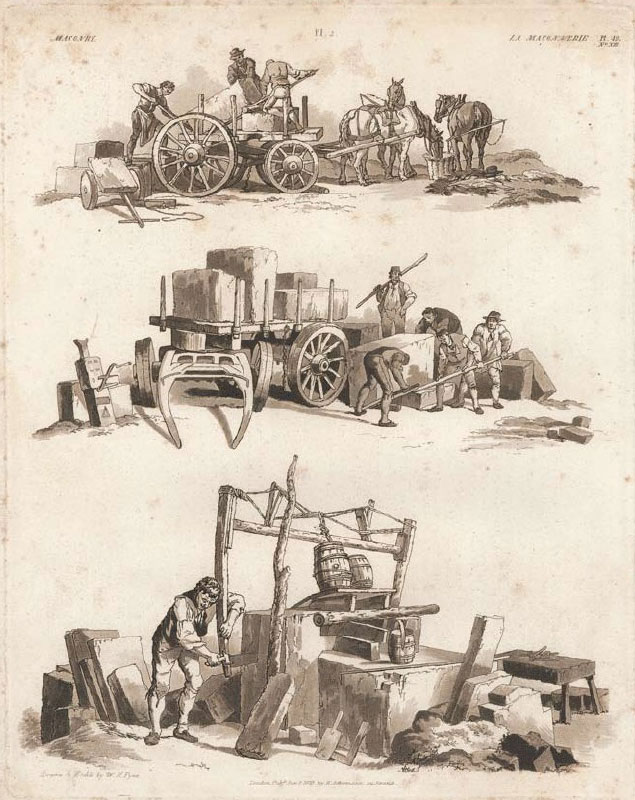

Aquatint

Aquatint. W. H. Pyne. Masonry from Picturesque Groups for the Embellishment of Landscape. (London: M.A. Nattali, 1845). c. 1823 (Printed by J. Hill, 1845). 11 1/2 x 9 1/8" (29.2 x 23.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. This particular plate was published some years earlier in January 1823. Pyne is given credit for the drawing and etching, and J. Hill is credited for the aquatint.

Aquatint is a form of etching. Developed in the eighteenth century, it was the first truly tonal system of ink printing. The cross-hatching used in relief printing and engraving had involved small marks that allowed black ink to appear to the eye as various shades of gray, but that did so by tricking the eye. Aquatint managed this by generating a printing plate with a fine array of cells etched to variable depths, so that the ink was actually put down in different thicknesses. The ink was manufactured so that a thin film looked pale, a thicker one darker, and, when finally thick enough, the deposit appeared black. Aquatint could portray tone in beautiful gradations.

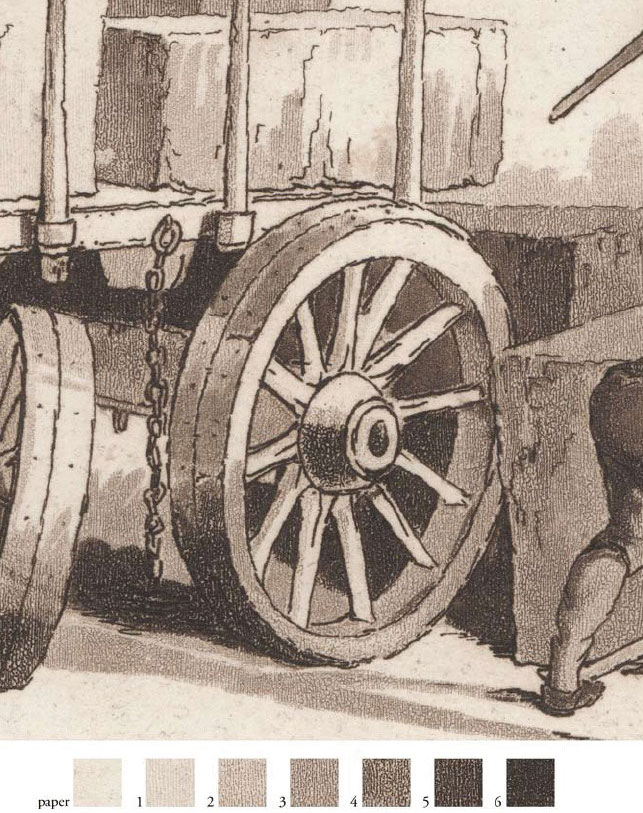

Detail from Aquatint. W. H. Pyne. Masonry from Picturesque Groups for the Embellishment of Landscape. (London: M.A. Nattali, 1845). c. 1823. (Printed by J. Hill, 1845). 11 1/2 x 9 1/8" (29.2 x 23.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. This detail—an eight-times enlargement of the wheel on the previous page—shows evidence of two aquatints: a fine one, which produced the gray tone in the center of this blowup, and a coarser one, slightly vertical, that managed the rest of the tones. The darkest part, at the bottom of the picture, shows evidence of needle work done through the aquatint to make an even darker tone.

It was used for hand-drawn prints in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and then was adapted to photogravure in the 1850s. The basis of an aquatint was a fine deposit of acid-resistant grains—usually asphaltum or rosin—applied in a random pattern to a copper plate.

The printer could spread these particles evenly with a device called a “dusting box” or could scatter them onto the plate more irregularly by sifting them through a piece of cloth, traditionally a sock, which could be squeezed or shaken over the plate to put down an aquatint grain in any desired area. Once applied, and set with heat, the particles would resist the etching chemical, protecting the original plate surface during the etch. If they covered more than 50 percent of the plate surface they tended to form a connected network, and the etching took place in the gaps in the net; if the aquatint was light, it was the etched areas that would form a network while the nonetched areas became separate points. In either case the result was a delicate pattern of pockets in the plate—tiny etched areas that could hold ink. After etching, the printer would remove the asphaltum or rosin grains with a solvent. He would ink the plate, then wipe it, and his wiping cloth or hand would run across the higher, nonetched areas without removing the ink from the pockets. If the etching was deep the tone produced would be dark; if the etching was light—only a few seconds or so—the tone would be pale and smooth. Complex pictures such as Pyne and Hill's were made by etching a single aquatint in many discrete steps, each deeper than the one before. To fully understand this we need to examine a magnified section of the plate.

Detail from Aquatint. W. H. Pyne. Masonry from Picturesque Groups for the Embellishment of Landscape. (London: M.A. Nattali, 1845). c. 1823. (Printed by J. Hill, 1845). 11 1/2 x 9 1/8" (29.2 x 23.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Detail from Aquatint. W. H. Pyne. Masonry from Picturesque Groups for the Embellishment of Landscape. (London: M.A. Nattali, 1845). c. 1823. (Printed by J. Hill, 1845). 11 1/2 x 9 1/8" (29.2 x 23.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

This four-times enlargement of Pyne and Hill’s print shows the delicate random pattern of the aquatint-generated cells. It also shows that the picture has a simple line-drawn skeleton, an initial drawing into which the tones generated by the aquatint have been fitted. The tones themselves do not gradate smoothly from one value to another but change in discrete steps. I have set small squares of the six visible tonal levels in the print, along with the plain paper base as the lightest step, below the detail. In fact there are eight tones in the picture: the paper, six levels of aquatint, and the dark value of the etched linear drawing. The print was begun as a plain etching—a line drawing made with a needle in a plate.

Once it was etched and a trial print or “proof” was made to check the drawing, the plate was cleaned and a superb aquatint was applied over the entire surface. Before any further etching was done, the areas of the picture that were to remain plain, unprinted paper were “staged out” by being painted over with a resist (probably asphaltum dissolved in turpentine). The plate was then given a short acid-bath etch, just enough to lightly etch between the aquatint grains the shallow cells that would produce the lightest printed tone we see—the tone in block 1, one step darker than the bare paper. The plate-maker then shielded the areas that were to retain that tone by painting them with the resist, and the plate was etched again. That bite went to a sufficient depth to produce the tone we see in block 2. And so the procedure continued until the plate had received six etchings, each with different degrees of staging of the plate surface and each to a different depth. Only once these were completed was all of the resist (aquatint particles and staging paint) removed and the plate proofed to see the results. Further corrections were still possible, using etching, drypoint, or even a fresh aquatint, but the bulk of the image was done through the initial linear etching, the single aquatint, and its successive etchings. Aquatint could produce smooth tonal areas with a grain so fine that it was completely invisible to the unaided eye. The process was fairly widely used, most often as a supplement to a conventionally etched picture. The tonal capacity of the aquatint was far greater than a hand-generated print could ever achieve. Photogravure, invented in the 1850s, was the process that harnessed the untapped wonders of the aquatint’s full tonal range.