- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

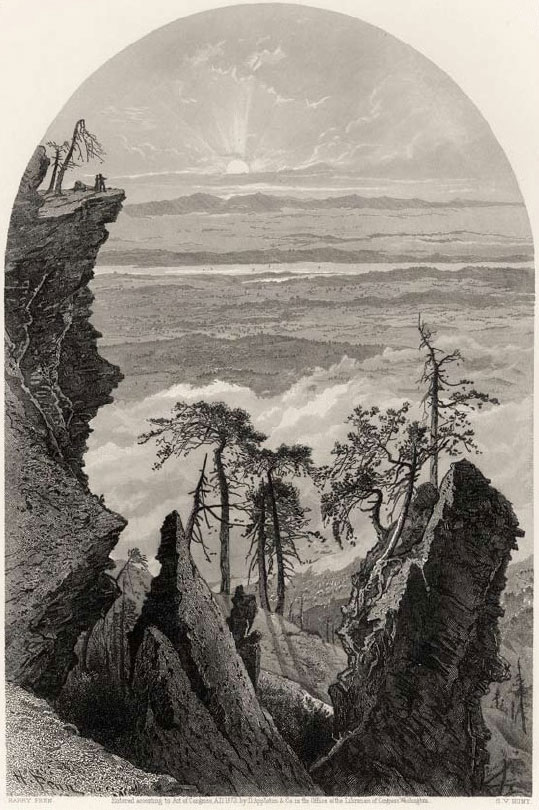

Steel engraving

Steel engraving. Harry Fenn. The Catskills from Picturesque America, Volume II (New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1874). c. 1870 (Printed by S. V. Hunt, 1974). Arched top: 8 7/8 x 5 15/16" (22.6 x 15.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Copper printing plates wear out with use. The abrasion of wiping and the pressure of printing can affect the plate quite rapidly: the edges of the incised grooves become rounded and the wiped plate holds less ink, so the print gradually becomes lighter through the successive impressions of an edition. One way to print intaglio in longer editions was to engrave the plates in steel instead of copper. Steel was difficult to work; instead of simply holding the burin by hand, the engraver often had to strike it with a hammer. The problem was compounded by the fact that a steel tool was being used to cut steel, but one characteristic of that material is that it can be prepared soft or hard—the steel burin could be tempered until it could cut the softer plate. Steel plates produced a new class of prints that look very different from those made with copper. They were called “steel engravings,” but a great deal of etching was almost invariably present as well.

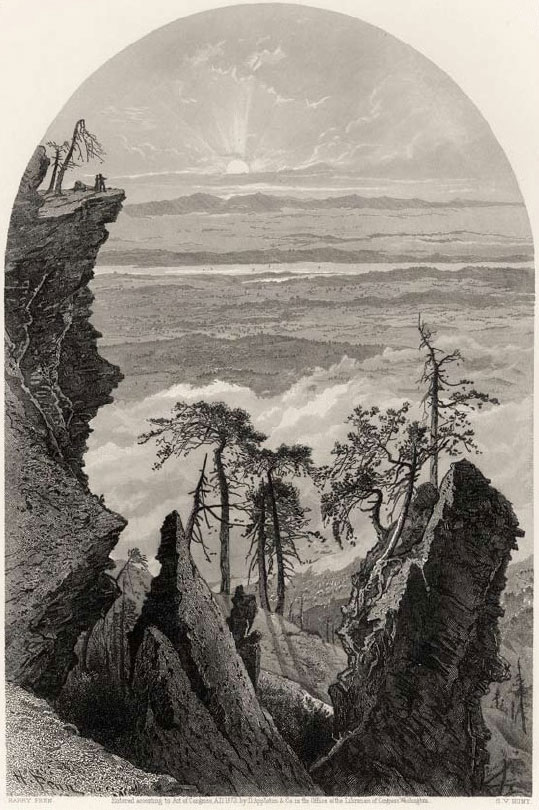

Detail of Steel engraving. Harry Fenn. The Catskills from Picturesque America, Volume II (New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1874). c. 1870. (Printed by S. V. Hunt, 1974). Arched top: 8 7/8 x 5 15/16" (22.6 x 15.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. In almost all steel engravings that depict a delicate pale sky, the appearance of tone is generated by the use of a burin guided by a straightedge. The two sets of lines in this detail, both made in that way, are angled at approximately thirty degrees to each other. This angle was chosen because overlapping linear designs often create disturbing “moiré” patterns, and printers learned that a thirty-degree difference minimized them.

Cuts made with a burin tend to curve in one direction only; a line drawn with an etching needle can freely change direction in a single stroke. These different lines can often indicate whether a print was made by engraving or etching. Almost every piece of steel engraving that I have seen includes a substantial amount of etching, so the process name is somewhat of a misnomer. Steel engravings were very popular in the 1870s and ’80s and often turned up in art books.

Steel engraving. Harry Fenn. The Catskills from Picturesque America, Volume II (New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1874). c. 1870 (Printed by S. V. Hunt, 1974). Arched top: 8 7/8 x 5 15/16" (22.6 x 15.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The usual practice in these volumes was mostly to use run-of-the-mill illustrations printed from wood engravings locked up with the metal type used for the text. Scattered throughout the book, though, would be lush steel engravings, printed on beautiful thick paper bound into the more humble letterpress signatures. This particular plate is from Picturesque America, a two-volume publication by D. Appleton & Co. Beautiful books like this one are sought out by print dealers who cut out the pages to sell as single prints in antique shops. It is a tragedy that this happens, but I am as bad as they are: the plate we see here is one of a half dozen or so that I cut out of my copy of the book, to use in teaching my graduate students about the pictorial history of ink on paper.