- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

Iris prints

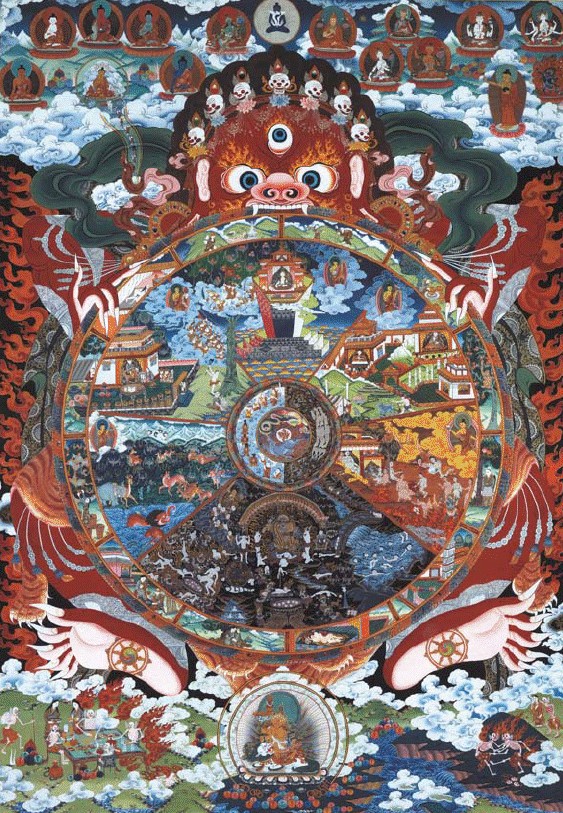

Iris print. Workshop of Romio Shrestha. The Wheel of Deluded Existence. c. 1995 (Printed by Laumont Editions, 1999). 21 1/4 x 15 3/4" (54 x 40 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. Courtesy Callaway Arts & Entertainment, New York.

The great digital machine that ushered in the computer age of fine printing was the Iris printer. These inkjet printers were developed in the late 1980s as proofing devices for offset presses. They enjoyed limited success in this role because it turned out to be extremely difficult to make their inkjet image closely resemble the ink-printed halftone image that came out of the large offset printing presses. There were other color proofing systems out there, and the Iris never could compete with them. What these machines did do was make magnificent photographic prints on a wide variety of papers. The Iris used a large, rapidly rotating drum to hold the paper and a set of jets to put down a fine spray of ink. These jets were connected to ink tanks by flexible hoses, which allowed them to move slowly along the drum, parallel to its axis, to cover the entire area to be printed. The machine could lay down both fine lines of ink or ink drops of different sizes in a stochastic pattern.

Detail of Iris print. Workshop of Romio Shrestha. The Wheel of Deluded Existence. c. 1995 (Printed by Laumont Editions, 1999). 21 1/4 x 15 3/4" (54 x 40 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. Courtesy Callaway Arts & Entertainment, New York. The stochastic dot pattern we see here, enlarged approximately twenty times from the Iris print, appears as cyan, magenta, yellow, and black dots. These tiny points of ink do not vary in value; a dot is either there or not. Because of this go-or-no-go system, any tonal variation must be generated by controlling the number of dots that go down in a given area.

In the beginning, the Iris inks were pretty much just water containing dyes similar to food coloring. The deposits were so delicate that any spot of water that fell on them would create a mark, and sunlight faded the image very badly. These difficulties were finally overcome with the development both of better dyes and of various coatings that absorbed ultraviolet light, and that were sprayed onto the prints to improve their stability. Iris prints began to get a foothold in fine-art printing, and at one point some ambitious marketeer decided to call them “Giclée” prints. This deeply stupid name has led many a purchaser to think they have some rarefied creature hanging on their wall when all it is is an inkjet print.

“Giclée” has now been applied to prints made with any inkjet printer, so the purchaser of one of these prints can’t even be sure of getting an Iris print. The Iris printer created, for the first time, marvelous photographic prints with highly saturated colors on a truly matte surface. Papers were made with matte surfaces for traditional, chemical color photography, but those papers had always produced inferior colors. The legacy of the Iris, which continues today in all the small- and wide-format inkjet printers, is to produce soft, matte yet intense colors, unlike any that had been seen before. Black and white photographers had the platinum print for matte images but there was no comparable method for color. If an Iris was made on a good rag paper, with the correct sizing, it could produce a tonal scale unmatched even today. Unfortunately a lot of poor pictures were made on fancy paper, complete with deckle edges and sold as high art, but when an Iris print was right, nothing could touch it for out-and-out image quality. There are still a few Iris printers in use, but the superb modern inkjet printers have driven the Iris into obsolescence.