- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

Collotype Process

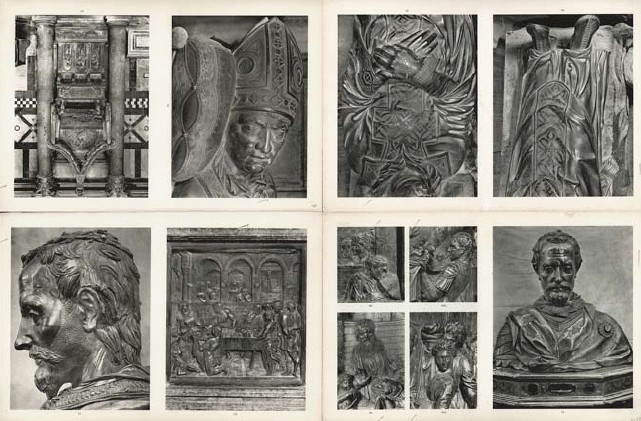

Collotype. H. W. Janson. Customer’s approval press sheet from The Sculptures of Donatello. (Printed by Princeton University Press, 1957). 1957. 25 1/2 x 37 3/8" (65 x 95 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. This was the customer’s approval sheet, and it was printed on October 24, 1957.

The printing plate for collotype was prepared by coating a sheet of tempered ground glass with a layer of gelatin containing a bichromate, as a light-sensitizer, along with other ingredients— every collotype shop had its own secret formula. This coating was applied hot, as a liquid. Once poured onto the plate, it was dried by leveling the glass, protecting it from drafts, and applying a gentle heat. Next the plate was exposed with sunlight to a continuous-tone negative (as opposed to the halftone-bearing negative used in letterpress printing), then washed in cold water to remove the bichromate and swell the gelatin.

Detail of Collotype. H. W. Janson. Customer’s approval press sheet from The Sculptures of Donatello. (Printed by Princeton University Press, 1957). 1957. 25 1/2 x 37 3/8" (65 x 95 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. One page from the Donatello sheet, reproduced at 85 percent of the size of the collotype.

This wash was critical because it produced a reticulated pattern in the gelatin, providing a fine grain that allowed tiny spots of black ink to appear to the eye as varying tones of gray. Where the plate had been heavily exposed the reticulated gelatin would not take up water, and so would accept ink; the less-exposed areas would absorb water, reject the ink, and consequently print lighter. Once processed, the plate could be dried and stored for some time before printing. When it was to be used, the glass plate holding the gelatin image was soaked in water and glycerin, drained, and placed on the bed of the press.

Detail of Collotype. H. W. Janson. Customer’s approval press sheet from The Sculptures of Donatello. (Printed by Princeton University Press, 1957). 1957. A detail enlarged twenty times from the collotype, showing the random grain of the reticulated gelatin.

It is an efficiency in book-making to print multiple pages at one time, on a large sheet of paper later folded and cut to make the individual pages of the book. When the book consists of type alone this is easy to do, since slight variations in the printing across the large sheet are usually invisible, and even if they are not, they have no effect upon the content that the printed page is delivering. When illustrations are printed, though, any variation has a strong effect on the picture. The images must all be handled in the same way, and tremendous technical skill is necessary to print eight illustrated pages consistently on a single side of the sheet.

Collotype became the most commonly used printing process for European postcards. This one is an example of a simple, single-impression card, printed in a blackish-green ink. Everett V. Meeks, whose name is stamped on the card, collected postcards and was the dean of Yale’s School of Art for thirty-five years.

We are used to this today, with our multicolor, highly mechanized offset presses, but when collotype was thriving, and twenty-eight-by-forty-inch glass plates were used to print fully illustrated pages, it was something of a miracle that all of the pictures could turn out well. The customer's approval sheet from The Sculptures of Donatello, printed by The Meriden Gravure Company in 1957, is nearly that size, and shows eleven photographs of sculpture by Donatello. The plate for it was exposed by sunlight to eleven continuous-tone negatives stripped into a single flat, then processed and printed in an edition of about 500 copies. After that many impressions, the plate would have been breaking down, from abrasion to the gelatin surface, so another would be made to print an additional 500 copies. A book such as this, if printed in 2,000 copies, might have taken four complete sets of plates. It is astonishing that cranky old collotype could produce sheets of such beauty.