- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

How Many Prints Can You Make With a Woodcut?

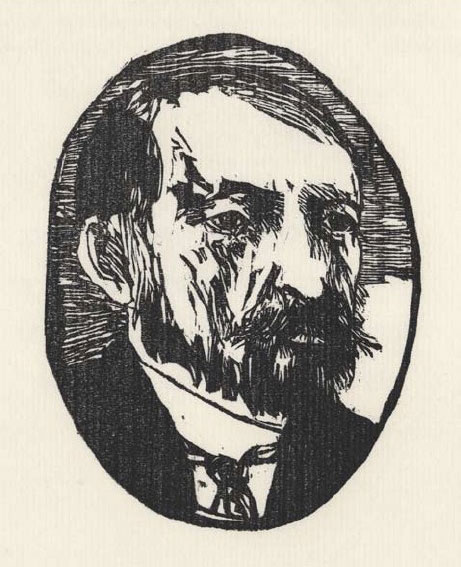

Woodcut. Leonard Baskin. Joseph Conrad. c. 1970. 5 1/4 x 4" (13.3 x 10.1 cm). © Estate of Leonard Baskin, courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York.

We often assume that woodblock printing takes place in a press, but far more woodblock prints have been made by simply placing the paper on the inked block and rubbing the back. The carved plank holding the image tends to warp and lose its flatness, and it doesn’t do too well under the pressure needed in a press.

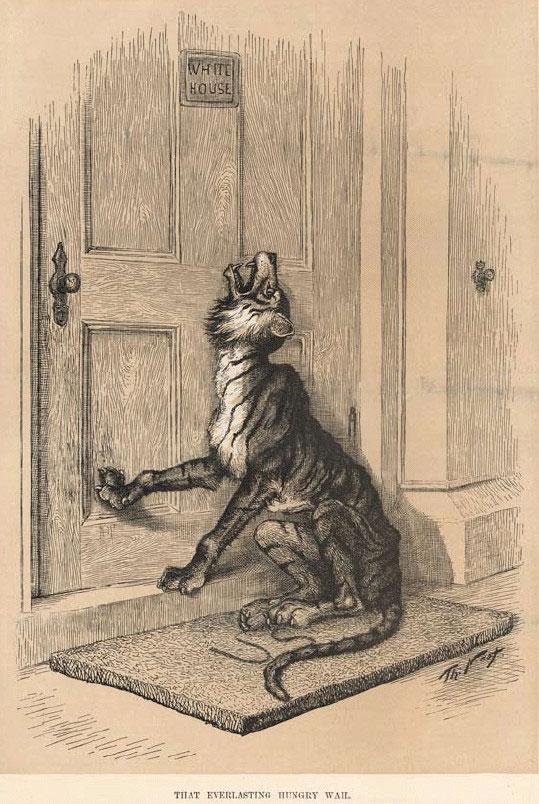

Letterpress from wood engraving. Thomas Nast. That Everlasting Hungry Wail from Harper’s Weekly. October 10, 1885. 14 3/16 x 9 9/16" (36 x 24.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. A two-color wood engraving by an anonymous engraver from a drawing by Nast.

However, the blocks for wood engraving had to be very hard; the favored material was boxwood, which is a small tree, so the printing blocks often had to be glued up out of small pieces. But boxwood is dense enough to lock up decently with type in a printing chase. Still more important, the height of the block is extremely stable, since wood undergoes little dimensional change along the direction of its grain when temperature or humidity varies. The wood could be carefully dried, accurately finished to type height, and cut to the size needed for illustrations.

The early, semirotary steam-driven presses could dependably print forms properly locked up with metal type and end-grain picture blocks. When presses became fully rotary, the printing was often done from a “stereotype,” a precise casting made from the type and picture blocks. Stereos were thin and could fit the curved shape of the printing cylinder. Far higher printing speeds were possible on these new presses, in which flat reciprocating surfaces were eliminated.