- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

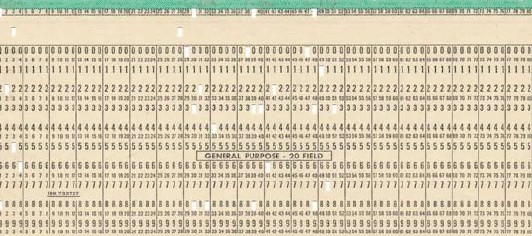

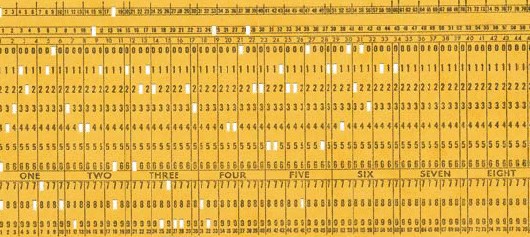

IBM punch cards

Punched paper with photo offset text. IBM Corporation. IBM punch card. c. 1956. Each: 3 1/4 x 7 3/8" (8.3 x 18.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The IBM punch card had its heyday as a data-storage tool from the 1930s to the 1960s. One interesting thing that these cards did, aside from storing data, was translate binary information into electrical signals. Small conductive brushes rested against the card as it was read. If a hole was present, a current flowed; if the paper was solid, it did not. The punched hole was really a switch, and this notion of a switch that was turned either on or off became the basis of the electronic computer. We have to understand some of the principles underlying these devices because the computer and its peripherals will shortly be handling every piece of photography and printing that is done.

Punched paper with photo offset text. IBM Corporation. IBM punch card. c. 1956. Each: 3 1/4 x 7 3/8" (8.3 x 18.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

I exaggerate a bit, because there will always be folks who use film and old printing presses, but they—and their work—are already firmly stuck on the banks of the technological river that is sweeping the rest of us away from our solid old analog roots. If we were to pick the best word to describe the precomputer age of technology, it would have to be “analog.” An analog is some physical structure that emulates the form of another. The tones in a black and white photographic negative are a simple analog of the illumination that fell upon that negative during the period of its exposure. The silver deposits change across the negative in continuous variations in density, with one tone smoothly turning into the next.

Punched paper with photo offset text. IBM Corporation. IBM punch card. c. 1956. Each: 3 1/4 x 7 3/8" (8.3 x 18.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

This analog is a simple one because color has been left out; by using black and white film we have chosen to select only a part of the incoming information for our record. That selection, however, is not only smooth and accurate but appears to be continuous and uninterrupted. Until we enlarge it so highly that grains of silver appear, we believe that we are seeing actual tonality in the negative. When such a “continuous tone” negative is digitally scanned into a computer, its information is chopped up into discrete values, each assigned to a particular point on the negative’s surface as a numerical record of the tonal density at that point. Because the computer is electronic, this digitization is in binary form, so that it can be handled by switches turned either on or off. The translation is very similar to the one we see on these IBM cards, with one, major exception: the data in the negative is translated into a tremendous number of values, far more than in the relatively crude cards we see here. Like halftone dots on the printed page, digital information must be plentiful, and must shrink below the resolution of our senses, if it is successfully to imitate the analog from which it derives.