- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

The Kodak Number 1

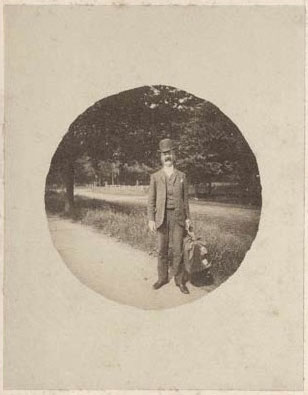

Gelatin silver print. Photographer unknown. Kodak #1 print. c. 1890. Page: 7 x 10 3/16" (17.8 x 25.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

If we think of the development of photography as some sort of evolutionary process taking the form of a branching tree, then we could say that the tree split, and grew a second trunk, with the development of George Eastman’s amateur cameras. Eastman cobbled up a system combining his own ideas with those of others and produced cameras that were sold preloaded with a roll of flexible film. The user exposed the roll, then shipped the whole camera, its film inside it, to the factory for processing. The film was processed, the camera was reloaded with a new roll, and camera and prints were mailed back to their owner. All the user had to do was aim the camera, click the shutter, and use the mail—all of the technical chores were taken over by Eastman’s company. These extremely basic cameras used a single-element lens and a single-speed shutter.

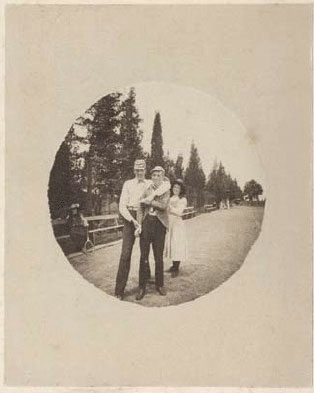

Gelatin silver print. Photographer unknown. Kodak #1 print. c. 1890. Page: 7 x 10 3/16" (17.8 x 25.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Because the lens was crude it did not cover the corners adequately so a round mask was placed in front of the film to crop them out, making the earliest Kodak pictures round in format. It was also a very wide-angle lens, which meant that as often as not the subject managed to be in the picture, despite the inaccuracy of the camera’s viewing system. The wide angle of view from such a short-focal-length lens produced a description of the world very different from the previous photographic norm. For centuries, painters had been structuring their pictures so that figures, buildings, and landscapes appeared “normal,” which is to say undistorted by a close point of view. We can even go so far as to say that the vision of the traditional painter was that of a photographer using a long lens. The Kodak camera, with its short-focal- length lens, distorted the perspective of a scene when compared to traditional pictures.

We can see this distortion in the two photographs shown: feet in the foreground turn down and enlarge as they approach the picture edge. Trees in the picture on the previous page go from very tall to very short as they run from left to right. The young woman in that photograph, who appears abnormally small compared to the two men in front of her, is not in fact so small; her odd size is a result of the picture structure. While her head is lower than the men’s, her feet also have risen up in the picture plane. Both these shifts of scale derive from the lens. In some ways we can say that the history of photography has been one of steadily shortening focal lengths. From the classical, distanced view of the painter, photographic description shifted to encompass wider and wider angles of view. Both Eugène Atget, the great French photographer who so often worked in cramped spaces, and George Eastman, the American entrepreneur, moved photography a huge step in this direction through their adoption of radically descriptive wide-angle lenses.