- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

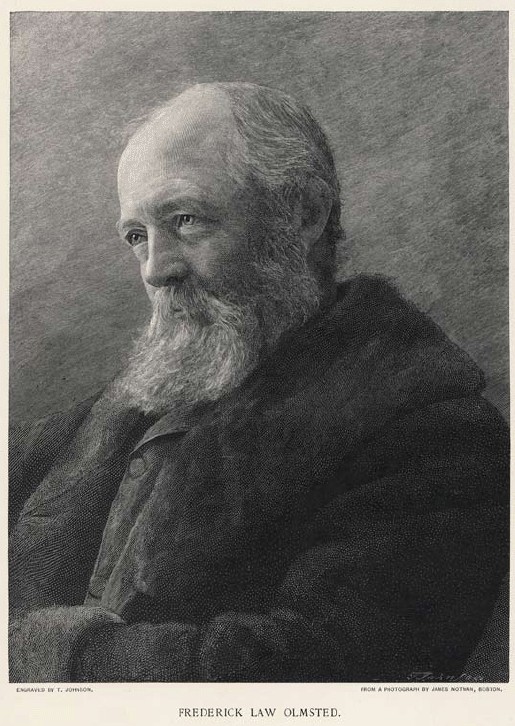

Wood-engraved photographs

Wood engraving. James Notman. Frederick Law Olmsted from The Century, Series 24, issue 46 (May-–October, 1893). c. 1893. 7 1/2 x 5 3/8" (19 x 13.6 cm). Printed by T. Johnson. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The invention of the dry-plate negative around 1880 made photographs radically easier to make. The subsequent development of practical techniques for mechanically translating photographs into ink vastly enlarged the potential for disseminating photographic imagery to an ever-larger audience. Once these two revolutions were in place, in the early twentieth century, photography’s lens-based descriptions became as ubiquitous and indispensable as written language.

The picture on the left originated as a chemical photograph—the photographer is even given a credit line—but the print we see was made from a hand-cut wood engraving. The sequence by which this happened went as follows: (1) the photograph was taken (probably around 1880) using an early dry plate. (2) This negative was printed with a light-sensitive coating that had been applied to an end-grain wooden block. (3) A carver laboriously engraved the block by hand, working with a burin and using the image printed on the wood as a guide.

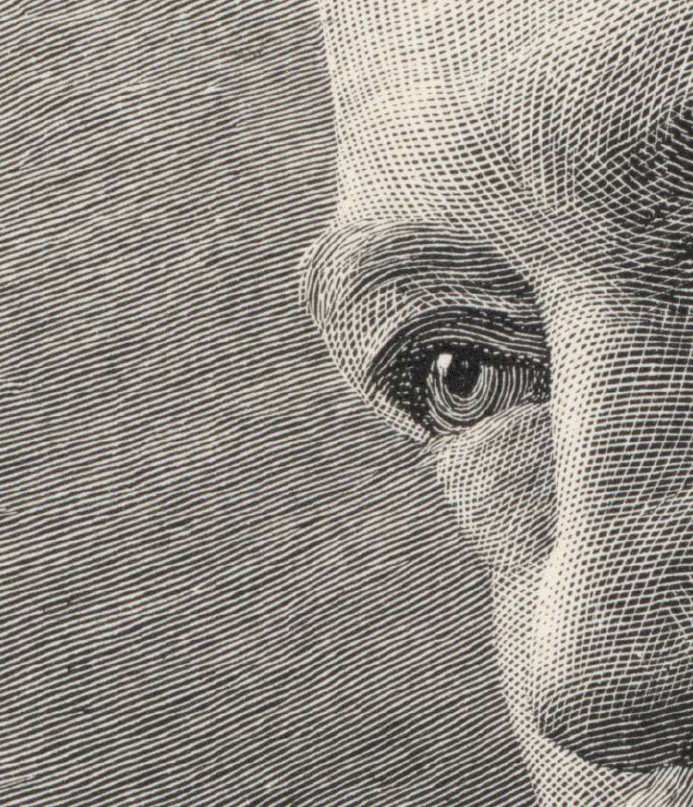

Detail of Wood engraving. James Notman. Frederick Law Olmsted from The Century, Series 24, issue 46 (May-–October, 1893). c. 1893. 7 1/2 x 5 3/8" (19 x 13.6 cm). Printed by T. Johnson. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson

(list continued from previous page) (4) The finished block was locked up with type in a chase. (5) This composite was used to generate a stereotype (a thin metal replica, shaped to fit a cylinder), and (6) this plate, along with a group of others, was mounted on the cylinder of a rotary printing press, to be printed at high speed for use in the magazine The Century. This detail of the previous plate, enlarged eight times from the size of the actual wooden block, shows the extraordinary network of lines that was hand engraved with no tools other than the guide photograph, a handheld burin, and a magnifying glass.

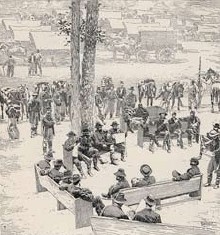

Wood engraving. Timothy O’Sullivan. General Grant with Staff at Bethesda Church from The Century magazine, vol. XXXIV, May 21, 1864. 1864. 5 5/8 x 5 1/4" (14.3 x 13.3 cm). Printed by Isaac Walton Taber. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Photography was mature by this time, and was replacing handwork in the task of gathering data for widespread dissemination by the printing press. The presses themselves were fast, driven by the equally mature steam engine. The odd part of the whole process was that the hand still played an important role in translating the photograph into printable form. It seems that this task of translation should have been easy, but it was actually extremely difficult. The technologies of photography and printing were both well advanced before the emergence of the simple dot-bearing halftone, which ultimately replaced hand engraving.

Timothy O’Sullivan. General Grant with Staff at Bethesda Church. May 21, 1864. As a mediocre half-tone, printed c. 1966.

Timothy O’Sullivan. General Grant with Staff at Bethesda Church. May 21, 1864. As a mediocre half-tone, printed c. 1966.

To this day the task of converting a photograph into ink is fraught with problems—a seemingly simple chore, it almost never turns out correctly. There are various ways in which this translation has been done and many challenges that have so often led the process astray. The fundamental problem is that photographs have tonal gradations that ink, when printed by relief or planographic processes, does not. Black ink is always black—it either goes down on the sheet and makes a black mark or it is not there and the paper is white. The solution to this problem has always been to break the picture up into small particles and to vary the size or number of those particles to emulate tone. The wood engraving we see here achieves this through an incredibly refined set of hand-cut lines. When these small marks cover a large percentage of the paper surface the tone appears dark; when they are small or widely separated, that part of the picture looks light. There are difficulties faced in carrying out this variation through mechanical means, with no assistance from the mind of such craftsmen as the engraver who made this block.