- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

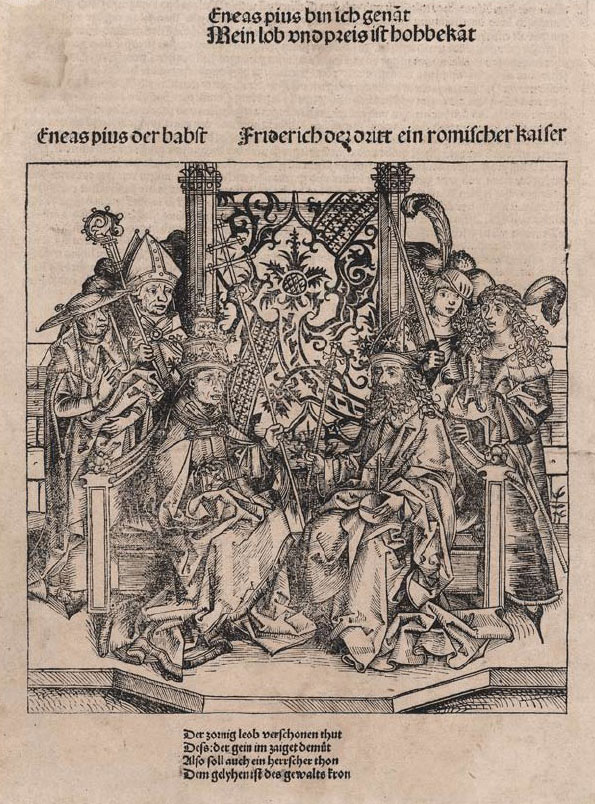

Woodcut and metal type

Letterpress from woodcut and metal type. Anton Koberger and the workshop of Michael Wohlgemut. King Friderich and the Roman Pope, page from the Nuremberg Chronicle by Hartmann Schedel. 1493. 13 3/8 x 9 15/16" (34 x 25.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. Because the side-grain block used for woodcuts was not stable enough to lock up well on the press with metal type, words and pictures were not usually printed together before the advent of wood engraving in the nineteenth century.

Letterpress from woodcut and metal type. Anton Koberger and the workshop of Michael Wohlgemut. King Friderich and the Roman Pope, page from the Nuremberg Chronicle by Hartmann Schedel. 1493. 13 3/8 x 9 15/16" (34 x 25.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. Because the side-grain block used for woodcuts was not stable enough to lock up well on the press with metal type, words and pictures were not usually printed together before the advent of wood engraving in the nineteenth century.

Since the very beginning of printing on paper, printers have struggled to accommodate words and pictures on a single page. Both types of images are pictures—the former symbolic and the latter representational—but the methods used to print them have been very different.

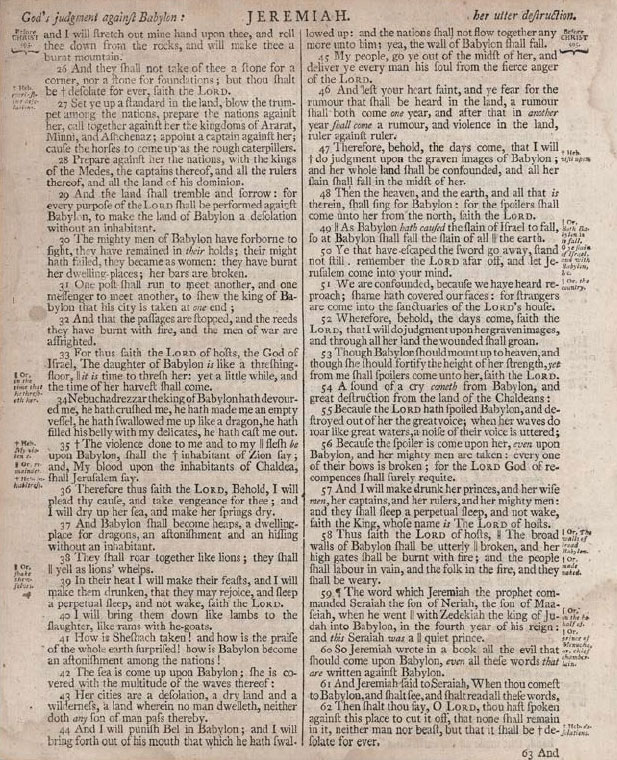

Letterpress from metal type. Mark and Charles Kerr, Edinburgh, printers. Holy Bible, page from Jeremiah 51. 1795. 9 11/16 x 8" (24.6 x 20.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Letterpress from metal type. Mark and Charles Kerr, Edinburgh, printers. Holy Bible, page from Jeremiah 51. 1795. 9 11/16 x 8" (24.6 x 20.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

This page, an early effort to combine words and pictures, was made by locking a woodcut into the chase along with the letters and furniture. This was a dubious practice: the woodblock could be made type high, so that the printing surfaces of both picture and words came to the same level in the press, but the block was flexible while the type was not. As the wedges used in the “form” (the printer’s name for the assembled contents of the chase) pressed the assembly together, the woodblock, at right angles to the direction in which it had grown in the tree, would compress.

Detail of Letterpress from metal type. Mark and Charles Kerr, Edinburgh, printers. Holy Bible, page from Jeremiah 51. 1795. 9 11/16 x 8" (24.6 x 20.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. k. Gift of Richard Benson.

Detail of Letterpress from metal type. Mark and Charles Kerr, Edinburgh, printers. Holy Bible, page from Jeremiah 51. 1795. 9 11/16 x 8" (24.6 x 20.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. k. Gift of Richard Benson.

The metal type, on the other hand, would hold its shape under pressure, so picture and letters were held with different degrees of firmness and the whole package was unstable. Such instability could be tolerated in a slow, manually driven hand press as long as the printer kept a close eye on the chase and its contents, but the system could never work once the presses ran at any sort of speed. The page from the Nuremberg Chronicle was made in 1493, well before the arrival of the steam-driven printing press, so it could be slowly printed by this union of side-grain wood and metal type. Three hundred and fifty years later, when presses were mechanically driven at high speeds, a different method for uniting words and pictures would be needed.