- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

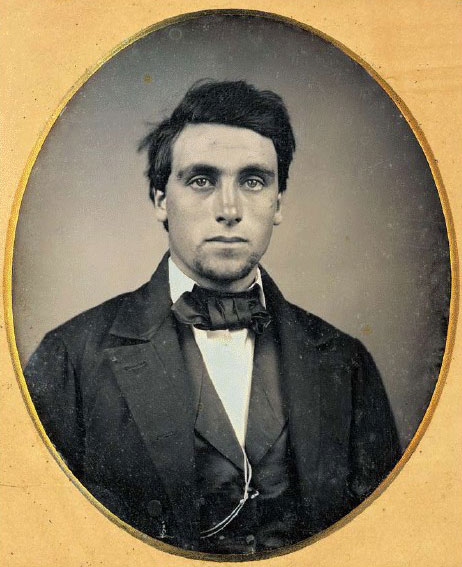

The Daguerreotype

Daguerreotype. Photographer unknown. Portrait of a young man. c. 1860. 3 1/4 x 2 3/4" (8.3 x 7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

All photographic capture methods from 1840 until the development of digital technology depended upon the sensitivity of silver compounds to light. By photographic “capture” I mean the generation of specifically lens-based images. Through the balance of the nineteenth century, many processes evolved for photographic printing, a number of them using not silver but other compounds responsive to the high levels of illumination that could be used to print photographic negatives by contact. But only silver salts were sensitive enough to record the relatively weak light that could pass through an image-forming lens. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s invention—a method of hardening asphaltum by exposure to light—came first, but it turned out to be a complete dead end for photography per se; it was too insensitive for use in a camera.

Daguerreotype. Photographer unknown. Sarah Anna Chace Greene and Her Children. c. 1850. 3 5/8 x 4 1/4" (9.2 x 10.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson

Silver dominated photography for a century and a half, and from the start it exhibited two completely different ways of making images. The first method in which a silver compound darkens directly as it is exposed is referred to as “printing out” and was essential to the earliest paper processes. The second, which uses the ability of some silver compounds to hold a latent image, invisible yet developable was the basis of the daguerreotype and of all of the glass and film processes that followed. It is of the utmost importance to recognize this miracle of some silver compounds that they not only respond to light in a manner that can be made permanent, but do so in two radically different ways.

Daguerreotypes were made by silver-plating a sheet of copper, then treating it with an iodine compound to produce a coating of light-sensitive silver iodide. After exposure the plate was subjected to mercury vapor, which condensed onto the latent image, most thickly where the light had been brightest. When the silver areas in a daguerreotype reflect a dark ground, the mercury appears as diffuse white, producing a positive image. After the formation of the mercury image, the plate was “fixed” with sodium thiosulfate, which photographers nicknamed “hypo.” As a final step the pictures were toned with gold, which stabilized them and made the image more robust. Since the metal support did not absorb these destructive fixatives, the daguerreotype avoided the fading that has always plagued paper photography, but all daguerreotypes had to be sealed to prevent tarnishing of the silver coating upon which the mercury image rests. The small frames, glass covers, and cases in which daguerreotypes live add a whole layer of physical protection.