- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

The daguerreotype's durability

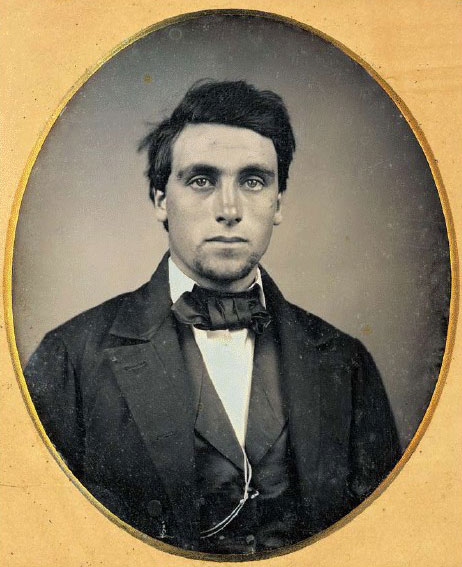

Daguerreotype. Photographer unknown. Portrait of a young man. c. 1860. 3 1/4 x 2 3/4" (8.3 x 7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The first practical photographic processes—the daguerreotype and the paper-based method—were at war in early photography. Sharp, clear, and permanent, the daguerreotype was perfection itself, while the paper image was rough, tonally poor, and subject to terrible fading. But paper would win the war, simply because it was cheap, easy to use photographically, and—above all—because it could generate multiple copies by printing a negative more than once. Since the daguerreotype produced a direct, camera-made positive, no negative was available for later printing.

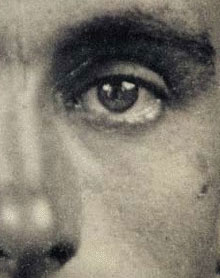

Enlargement of Daguerreotype. Photographer unknown. Portrait of a young man. c. 1860. 3 1/4 x 2 3/4" (8.3 x 7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. A seven-times enlargement from the original, showing the seamlessness of the daguerreotype’s description.