- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

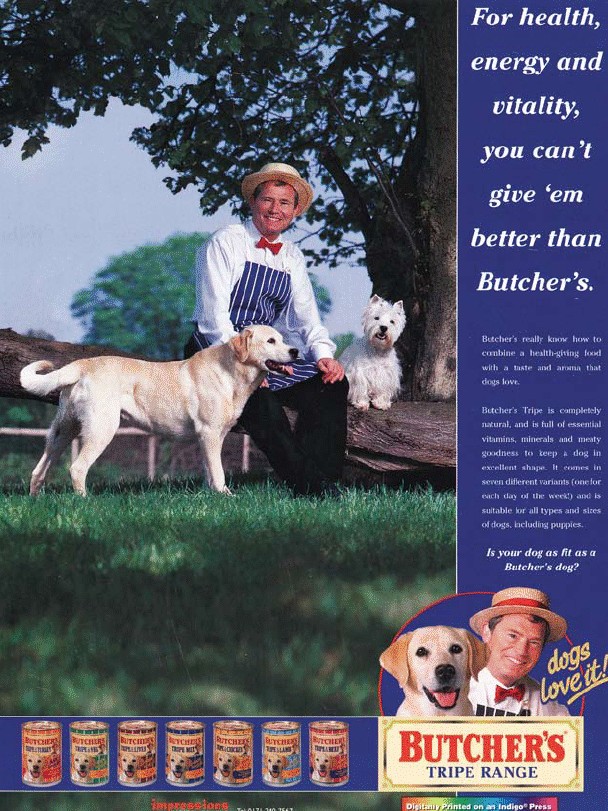

The Indigo printer

Indigo print. Impressions Digital Color. Butcher’s Tripe Range. 2006. 10 5/8 x 8 1/8" (27 x 20.7 cm). Printed by GHP (Gist/Herlin Press). 2006. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. Proof for an advertisement.

The computer has altered all phases of printing but one aspect of the practice has remained stable since books were first printed: the designing, printing, and binding of a book in an edition that can then be marketed. The publisher puts up the money; the paper merchant, printer, and binder all get paid, and sometimes the author even gets compensation too, but all of these funds are handed out at the publisher’s risk that the book won’t sell. The economics are shocking to many photographers who naively want to have a book of their work published, because the actual making of the book only costs about 15 percent of the retail price (and that’s for a really well-made book!). Many publishers regularly lose their shirts on books, and only stay in business because some of the titles they publish hit the big time and make up for the losses.

Detail of Indigo print. Impressions Digital Color. Butcher’s Tripe Range. 2006. 10 5/8 x 8 1/8" (27 x 20.7 cm). Printed by GHP (Gist/Herlin Press). 2006. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The dot used by the Indigo printer looks identical to the dot used in conventional offset lithography.

There is an old tale about a publisher who wins the lottery, and instead of retiring decides to keep publishing until the money is all gone. The stubbornly persistent practice here is that of printing the entire edition at once. This habit can be traced back to preparatory costs and the need for printing presses to be tuned and “made ready” before they can print well. That preliminary work is so expensive that it is only undertaken when a large edition is to be printed. If we print 5,000 sheets on a multicolor offset press, that work might cost about $3,000, or sixty cents a sheet. If we use the same technology to print only five sheets, the run will still cost at least $1,000, because, even though we use much less paper, the prepress work and makeready remain the same. For the small edition the cost per sheet would then be a horrifying $200.

The computer might change this. One specific piece of technology that could do so is the Indigo press, which is now owned and sold (or leased) by Hewlett-Packard. This press is an offset press, still printing on a blanket from an ink-bearing plate, but the plate is electronic and can change its data set with every revolution of the press. That innovation is combined with the equally remarkable one of an ink that completely leaves the plate and blanket with each impression, so no residue remains from sheet to sheet. Rather than having to print the same page repeatedly between make-readies, the press can print the pages of a book sequentially, one after the other. This innovation permits the printing of single copies of a book at a reasonable cost. This technology, like that of the production-level color copiers, can produce books on demand. Huge inventories, storage warehouses, and publisher’s risk could all disappear if this practice became widespread. Even more important, such a development would support the making of books that are only viable for a small audience.