- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

Long-edition rotogravure

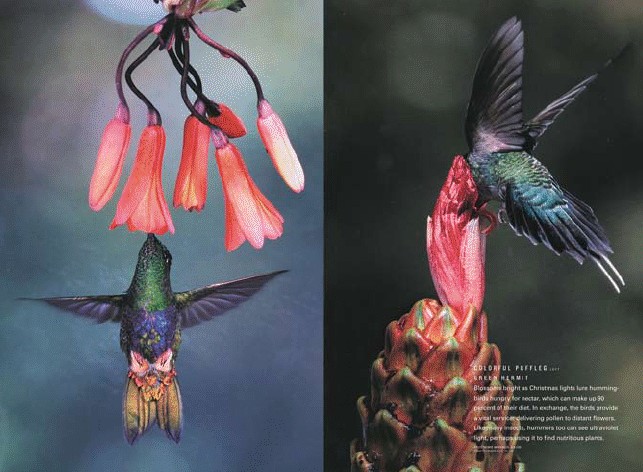

Web press rotogravure. Luis A. Mazariegos. Eriocnemis mirabilis (left) and Phaethornis guy (right) from National Geographic, January 2007. c. 2006. 10 x 13 3/4" (25.4 x 34.9 cm) each. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Luis A. Mazariegos

This is a spread from National Geographic. The publishers of this venerable magazine have long been dedicated to high-quality production, and have sought to maintain this quality as the size of the print run keeps growing. The solution, surprisingly enough, has been to print in gravure, the oldest of the ink-printing systems for photography. There is gravure in its early flat-plate stage, where the inking and wiping were done by hand. Then gravure’s rotary version's screened images were etched to variable depths and printed in longer editions with mechanical inking and printing. Almost all applications of gravure died out as offset became dominant, but one remained: this is magazine work in beautiful color, printed in editions in the many hundreds of thousands.

Detail of Web press rotogravure. Luis A. Mazariegos. Eriocnemis mirabilis (left) and Phaethornis guy (right) from National Geographic, January 2007. c. 2006. 10 x 13 3/4" (25.4 x 34.9 cm) each. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Luis A. Mazariegos. This detail shows the soft gravure printing dots, which vary in strength as well as size. The older, rectilinear dot pattern generated by a gravure screen has given way to circular, laser-etched printing cells.

The cylinders used for this kind of printing no longer carry a plate but print from copper electroplated onto a chrome cylinder. After the print run is completed, the copper is removed, a new layer of the metal is electroplated on, and the information for a new publication is etched into it. This etch is done directly, with a laser, instead of with the old carbon tissue. It might cost $2,000 to make a single cylinder, and a set of sixteen pages might require eight of these, but once they are made, the printing cylinders can print a million copies without wearing out, and do so with absolute consistency.

The machines that do this are immense, often printing in multiple units so that all of the signatures are assembled into a complete publication in one operation. The terrific cost of preparatory work becomes practical when it is distributed over a huge edition. A set of cylinders might cost $100,000 for a single edition, but if a million copies are printed, that cost amounts to only a dime a copy. Gravure lives on, making beautiful pages, in the surprising niche of lush, extremely-long-edition color printing. It is a little like the steam engine. This was the prime mover that drove the industrial revolution, in stationary engines running factories and in locomotives carrying huge loads for pennies a mile. Gradually these old vapor-based machines were driven to obsolescence by the internal combustion engine, burning gasoline in cars and diesel fuel in trains. Most people don’t realize that steam still lives, hiding in huge electrical power plants, where it drives the turbines that make 90 percent of all the electricity used in the world. The heat source might come from atomic reactions, and highly advanced turbines might convert the heat to work, but the same old steam powers a large part of our society. Odd hiding places can occur where old technologies live on in new and important roles.