- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

Pochoir

Collotype. Rembrandt. The Officer’s Wife. 1636. 10 7/8 x 8 1/4" (27.6 x 21 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. Collotype was used for process-color reproductions but the color impressions seldom registered properly. When correctly done, as in this reproduction of Rembrandt’s painting The Officer’s Wife, process collotype could be great, but pochoir is the more common form in which collotype was used to make color pictures.

Collotype. Rembrandt. The Officer’s Wife. 1636. 10 7/8 x 8 1/4" (27.6 x 21 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. Collotype was used for process-color reproductions but the color impressions seldom registered properly. When correctly done, as in this reproduction of Rembrandt’s painting The Officer’s Wife, process collotype could be great, but pochoir is the more common form in which collotype was used to make color pictures.

Collotype was often used to print the black and white skeleton for hand-colored prints. Called “pochoir” prints, these were usually made on good acid-free paper, then colored with stencils. They were most often made for the decorative market but also have a long history of turning up in books. The technical problem in hand-coloring is that the monochromatic framework that holds the applied color must be pale in those areas to be colored. This means, for example, that a pale blue or red tone, which would normally become a light gray in a black and white reproduction, must print as white—the gray would make the applied color “dirty.” Collotype was suited to pochoir for two reasons: its random grain was invisible to the eye, so there was no halftone dot to make the owner think it was a plain old reproduction, and the printing plate was generated from a continuous-tone negative, which could be made with a filter that eliminated most of the dominant color in the original.

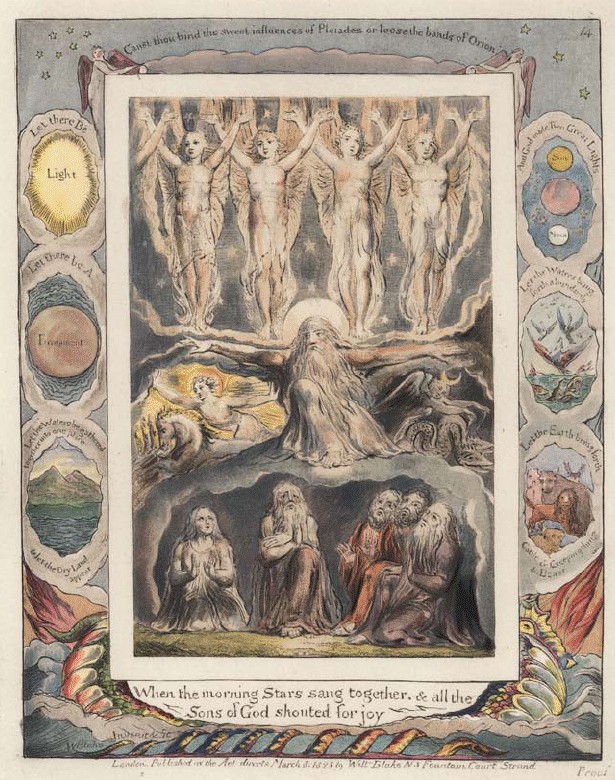

Pochoir. William Blake. When the Morning Stars Sang Together from the Book of Job. 1825. 8 x 6 3/8" (20.3 x 16.2 cm). Printed by Trianon Press. 1976. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. This print is a hand-colored collotype proof of a Blake engraving that was colored by someone other than Blake himself.

If the print being reproduced was heavy in the reds, a red filter could be used to make the negative and those areas would be light, allowing the hand coloring to show. The difficulty here was that, if the print had any blues, greens, or cyans in it, they would be rendered dark, making the hand-coloring for those areas worse. This could be somewhat countered by making exposures through two filters—we called it “split filtering”—but even so a good deal of handwork was necessary to get all the colors to disappear. When process color printing was developed, using the three subtractive primaries, it turned out to need a fourth printer using black ink. The task of eliminating color densities in this black printer was a huge challenge.

Detail of Pochoir. William Blake. When the Morning Stars Sang Together from the Book of Job. 1825. 8 x 6 3/8" (20.3 x 16.2 cm). Printed by Trianon Press. 1976. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The pale and open black and white impression of the collotype is visible in this enlarged detail.

In the older pochoir a solution had been cobbled up through imaginative filtering, careful developing of the negative, and then skilled handwork to complete the job, but when color was printed from the primaries, and a skeletal black was added, making this black printer right was almost impossible. One of the most amazing benefits of digital technology in the printing trades is that the computer can look at any point in a picture, evaluate the color data present there, and easily eliminate any values that are not neutral gray. By doing this across the entire data field of the picture, the printer can generate a file in which only the neutral values are present—the perfect attenuated-black basis for a color print. This new technology would have been perfect for pochoir but it became available at the very moment that hand-coloring disappeared altogether from printmaking.