- Relief printing

- Intaglio and planographic printing

- Color printing

- Bits and pieces

- Early photography in silver

- Non-silver processes

- Modern photography

- Color notes

- Color photography

- Photography in ink: relief and intaglio printing

- Photography in ink: planographic printing

- Digital processes

- Where do we go from here?

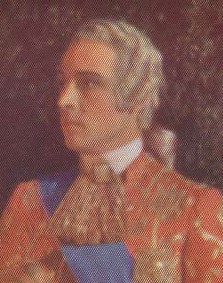

Process color in relief printing

An early color reproduction, using a primitive linear screen instead of the halftone dot. This image was supposedly the first color photograph transmitted by wire, in 1924. Reproduced from A Half Century of Color, by Lewis Walton Shipley, published by the Macmillan Company in 1951. Reproduced in approximately actual size.

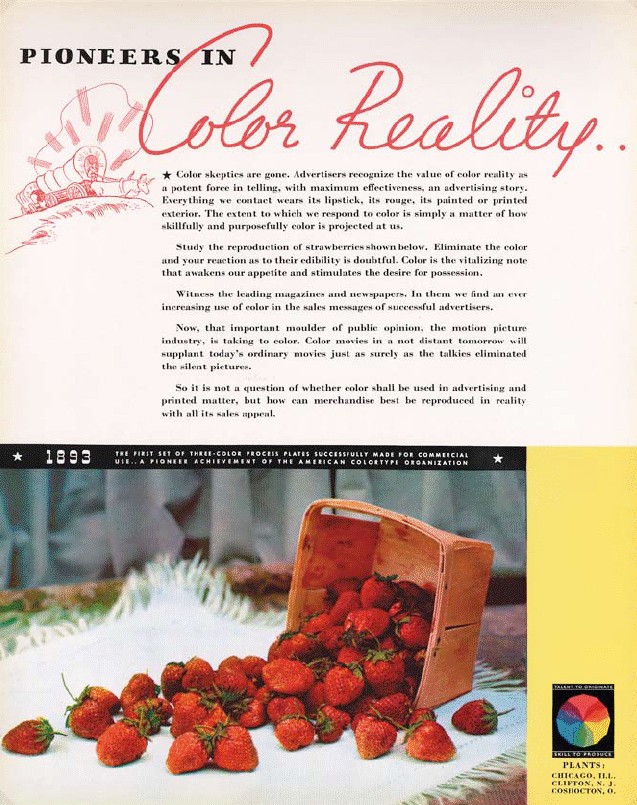

The development of color printing was entirely due to the belief that you had a better chance to sell someone something they didn’t need if you advertised it in color rather than in drab old black and white. The theoretical basis for color printing was laid out by James Clerk Maxwell in the mid-1800s, and decades of work in chromolithography had demonstrated the social power of ink images in color. By the 1940s color halftones were making their mark in magazines and books, printed by a method called “process color,” which was becoming firmly established. A key element in the spread of color was the construction of multiunit printing presses that could lay down all four process colors—the subtractive primaries of cyan, magenta, and yellow, plus black—in one pass.

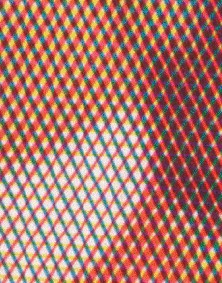

An eight-times enlargement from the print on the previous page, showing the screen pattern, which varies in line width to increase or decrease tone. This print resolves the problem of the moiré patterns by not using a black printer, reducing the number of screens to three.

The color reproductions printed with letterpress were never very good, but color had such commercial power that all printing technologies ultimately became color mediums. From its introduction before World War II, color printing grew so robustly that by the 1970s the printing press manufacturers—by that time making letterpress, offset, and gravure presses—were building more and more presses that printed four colors at once. Today, the single-unit press is an anachronism and huge, expensive, four- and five-color behemoths are everywhere. They crank out books and magazines and above all marketing catalogs in huge numbers. Today the process is usually photo offset lithography but its roots lie in letterpress, where the simple old copper halftone was refined to print three primaries in register to give the illusion of full color.

Process-color halftone print. Photographer unknown. Pioneers in Color Reality. 1936. 13 3/4 x 11" (34.9 x 28 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. From the trade magazine Advertising Agency, September 1936.

Idealized three-color printing, using cyan, magenta, and yellow, never worked properly because it produced an inadequate black, so right at the start a fourth impression, in black ink, was added to the “process” method, which then became known as CMYK printing. It’s critical to remember that color photography itself was still being worked out in the 1930s and 1940s; only after World War II did chemical color photography become first-rate and widespread. Color in ink was never top-notch until the development of the computer. Designers and publishers of art books tore their hair out trying to make fine color reproductions, and even now, when the technology of printing is completely embedded in the digital stew, pictures often turn out badly.